WASHINGTON – Rank-and-file members of rail labor are critical of a paragraph in the Presidential Emergency Board report that says railroads believe their workers have not contributed in any way to the industry’s record profits.

The Presidential Emergency Board, whose duty was to help settle the contract impasse between unionized workers and the U.S. railroads, this week summarized the positions of railroads and labor unions in its report outlining its contract recommendations.

“The Carriers maintain that capital investment and risk are the reasons for their profits, not any contributions by labor. The Carriers further argue that there is no correlation historically between high profits and higher compensation, either in the freight rail industry or more generally. To the contrary, one of the Carriers’ experts maintained that the most profitable companies are not those whose compensation is the highest. The Carriers assert that since employees have been fairly and adequately paid for their efforts and do not share in the downside risks if the operations are less profitable, then they have no claim to share in the upside either,” the report says.

Railroaders objected to the notion that they don’t help produce profits, as well as the assertion that they don’t share in downside risks. The paragraph, shared widely on social media, drew immediate reaction from railroaders who worked through the pandemic and have not had a raise since 2019. Some of their responses:

“Here’s what the carriers think about our contribution to their success.”

“Man, we went from essential to completely useless in a short amount of time.”

“Let’s all stop working and test this theory.”

“Don’t share in the downside? What do you call furloughed employees? I guess having to find another way to feed your family until the upside comes back, doesn’t count?”

“Last I checked ‘capital investment and risk’ isn’t moving their freight.”

“This should be printed out and hung in every depot….so nobody forgets what management REALLY thinks of us.”

The Association of American Railroads, CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern, and Union Pacific declined to comment and referred questions to the National Railway Labor Conference, which is the industry’s contract negotiations arm. BNSF Railway did not respond to a request for comment.

“The railroads value employees’ significant contributions to moving the nation’s freight. Rail employees work hard, and the railroads’ presentation to the PEB repeatedly emphasized that employees should receive compensation increases that appropriately reward those contributions,” the National Railway Labor Conference said in a statement.

The Class I CEO’s typically begin quarterly earnings calls by thanking employees for their contributions. And at an investor conference yesterday, NS CEO Alan Shaw called employees the railroad’s “most precious resource.”

The three-member Presidential Emergency Board, working under a 30-day timeline, sifted through 10,000 documents the railroads and labor unions submitted as part of the process. The board’s summary misconstrued some of the points the railroads made, including the fact that railroaders are the heart of the industry and deserve fair compensation, according to a person familiar with the matter.

The crux of the dispute over raises, the industry says, concerns how “fair compensation” should be defined.

The board recommended a 22% wage increase, along with $5,000 in service recognition bonus payments, over the five-year life of the contract retroactive to Jan. 1, 2020. That was below the 28% increase the unions sought, but above the railroads’ 16% proposed wage hike.

The unions have argued that a wave of layoffs that began when U.S. railroads began implementing Precision Scheduled Railroading operating models in 2017 means that remaining workers should receive compensation in line with their increased workloads.

The railroads argue, however, that the increases in productivity are the result of capital investments in technology and changes to operations such as moving more tonnage on fewer but longer trains, which requires fewer locomotives, shop workers, and train crews. There was not, the railroads say, a corresponding increase in skills of employees that would justify a productivity-based raise.

Rail workers also disagreed with the railroads’ contention that workers aren’t exposed to downside risk and therefore shouldn’t be rewarded when profits rise. Railroaders note that they are furloughed when traffic goes down and therefore are exposed to downside risk.

“I find the idea that employees somehow aren’t exposed to fluctuations in demand is inconsistent with the data,” says Jason Miller, an associate professor of logistics at Michigan State University.

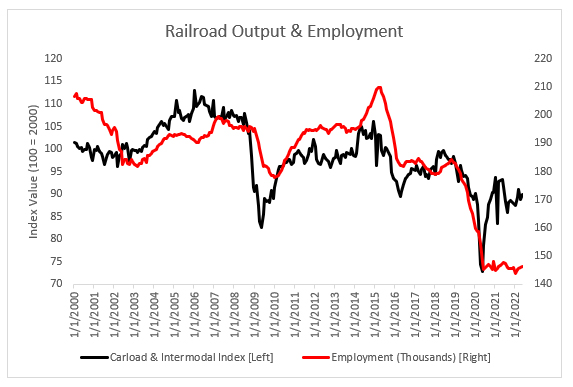

Miller compared Bureau of Transportation Statistics data for carloads and intermodal loads with rail employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data show that rail employment typically rose and declined in line with traffic volume — until 2020.

“When we calculate labor productivity as this weighted carload and containerload index over employment, we can see a tremendous surge of labor productivity since the pandemic hit,” Miller explains. “However, this labor productivity surge differs from in the mid-2000s or in 2018. Those two productivity surges occurred because volumes grew yet employment remained relatively the same. In contrast, the 2020-2022 labor productivity boom has occurred despite weighted output not reaching 2018 levels; rather, it is due to employment having been cut so much.”

This paragraph in a nutshell shows what is wrong with this country. The management view expressed here is widespread not just in the rail industry but all across the labour force. When is management going to realize that we are NOt the enemy, but a vital part of their company without which there would be no income for them to profit from. The adversarial relationship between labour and management has not served any of us well,

You want to reform the rail industry and begin to solve it’s problems? Start by getting rid of the mindset that short term profits and this quarter’s results are more important than the long term health of the company. Get rid of those who are only in it to milk the company for all it’s worth, and who would kill it off in a heartbeat if they could make money doing so. Replace them with people who are willing to think about where we’ll be fifteen or twenty years down the road.

Certain industries, transportation, vital metals, energy, electronics, etc should be considered as vital to national security and protections put in place to prevent the sort of short term management that has taken hold in the rail industry. Let the hedge fund people take their unsustainable business models elsewhere, somewhere the collapse of their victims doesn’t negatively affect the entire US economy.

It wasn’t that long ago that the rail industry was actively adding capacity and chasing after business, focused on a bright future where railroads were gaining market share. We need to get back to that.

The workers are the railroad, foster pride in them it will be rewarded

The fact that the people charged with shaping public perception of railroad companies are avoiding comment speaks volumes. Or carloads. Perhaps unit trains.

“The Carriers assert that since employees have been fairly and adequately paid for their efforts and do not share in the downside risks if the operations are less profitable, then they have no claim to share in the upside either,” the report says.”

It seems to me that the executives are also very, VERY well compensated for their efforts as well, but somehow they get the rewards? What do you call furloughs? And what risks are they taking? Its not like Fritz, Farmer, Foote, and whoever is at NS are putting in their own personal funds toward a project. And if management claims they are taking the risks and want to be rewarded, then by god let them be accountable for when the risks backfire! How many heads have rolled in this industry during the latest service ( or lack thereof) debacle? None that I know of.

How do you push for a brand new yard, get halfway done and then decide you dont need it, have take a writedown, and still have your job after making a 298 million dollar error?

Railroad “mangement” (an oxymoron if there ever was one) certainly has a talent for shooting themselves in the foot and putting that foot in the mouth.

The assertion that labor is only a cost and not asset to profitability is rampant in America. It is the reason that so much of manufacturing has been sent off shore (and now we are trying to get it back). It has hollowed out American working people’s income and broken a large part of the social contract which is reflected in our current political dysfunction. It is the self justification for managements “brilliance” and large over payment. It is a lie, and it will destroy America’s capitalist economy.

I was just out last weekend seeing a lot of abandoned lines plus some operas. Let’s see–Reading, Lehigh Valley, New York, Ontario & Western, Lackawanna, New York Central, Boston & Maine. I don’t think it’s that profitable an industry and Joe Biden intends to take us back to the days of Jimmy Carter. Yes, everything depends on the people doing the work—but so did all those lines I just listed with their abandoned lines. Sorry, but the re-arrangement of work (a/k/a E Hunter Harrison mania) was something management did. Longer, slower trains with mid-train helpers—tho’ every so often someone slips up and there’s an imbalance as in the CSX stack train at Palatine Bridge at 10:15am last Sunday with TEN engines.

These days, I long for the “good ol’ days of Jimmy Carter”…

Most railroaders do not share as their productivity increases. Lets assume that the average train is 7500 feet long. Engineers and conductors should receive additional pay for longer trains, for example:

7501 to 10000 feet……a 2 % pay increase for that trip;

10001 to 12500 feet..a 4 % pay increase for that trip;

12501 to 15000 feet…a 6 % pay increase for that trip;

over 15000 feet…..a 10 % bonus.

This would do two things, 1. reward crews for handling longer trains, and 2. encourage railroads to run trains with manageable lengths (that fit yards and sidings).

Damn, all that time and effort shot to hell because of one paragraph stating the truth about the railroads. I see picket signs in the near future.

Like the one quote says so eloquently. “ let’s stop work and test this theory” Then see how much labor contributes to the organization as a whole. They can’t make money if their freight doesnt move,and the country could implode if they don’t either, they’ve professed that many times over. So which is it railroads? Are the people who move the freight useless or do they actually provide something that contributes to the bottom line? We shall see.

It is darn fool statements that will come to bite everyone in the a**. The PEB was stupid to put that in the report and the carriers were even more stupid to state that in the first place. Are you stocked up on necessities I certainly am.

If Presidential Emergency Board report accurately reflects the position of railroad management, then surely that should have come up in negotiations and not be a surprise to union leaders. Note, however, that my statement in no way expresses a agreement with such a position, which I believe railroad hiring practices contradict.

“The Carriers assert that since employees have been fairly and adequately paid for their efforts and do not share in the downside risks if the operations are less profitable, then they have no claim to share in the upside either,” the report says.”

No downside effects to losses huh? How about losing ones job? That seems pretty downside for the rank and file to me.

If was an employment prospect and saw this in the press, I would turn and walk away.

On the flip side, this is a tacit admission that the Class 1’s efforts to reduce ratio wasn’t about better service, it was strictly about the profits. No matter how they they claim to want better service and “growth” (laughs), it had nothing to do with either.

If pay doesn’t matter every ceo should take a cut in pay.

Typical error when trying to combine 10,000 documents down into a single paragraph.