I have a confession to make: I’m an ops noob. I’ve been a model railroader for more than 30 years and have worked for Model Railroader magazine for 15. I edited Jerry Dziedzic’s “On Operation” column for years and Andy Sperandeo’s “The Operators” before that. And I know my way around a throttle. But a road trip organized by friend of the magazine Joe Russ on a recent warm, sunny April day was actually my first operating session.

Joe invited MR editor Eric White on the day-long road trip to two layouts in southwest Wisconsin, but Eric was already booked for that weekend. Since I had previously expressed interest in a hands-on operating session, Eric gave Joe my name, and I jumped at the opportunity.

It was a breezy and brisk Saturday morning when I met Joe, Rich, Dave, and Mark in a park-and-ride lot near Kalmbach’s Waukesha, Wis., offices. We piled into Rich’s SUV for the two-hour drive to the first layout on our schedule, in Reedsburg, Wis. Though they all knew each other, but not me, my four car-mates made me feel welcome. We discussed our home layouts, favorite railroads, Wisconsin Dells tourist attractions, and past ops road trips. Joe told of the time when, on the way home from an operating session, his car got two flat tires in the space of 10 miles. Little did I know this tale was an omen.

My first operating session: First stop, Montana

We met up with the rest of the group, who joined us from all over the state, at the first stop, Alan Schroeder’s HO scale BNSF Marias Pass Division. This sprawling, multi-deck, “mushroom” style layout models Northwest Montana between 1985-1995.

After briefing the assembled operators in his comfortable basement crew lounge, Alan let us draw numbered chips to determine who would get to choose their job first. Beginner’s luck – I drew number 1. Though I thought switching a local would be a lot of fun, I knew my limits. I asked for a through freight so I could get used to the layout’s control system, the layout itself, and operations in general before I had to figure out waybills and uncoupling. Joe offered to act as my conductor, since he was familiar with the layout.

I took control of my train, a hotshot overhead intermodal freight, from the trainmaster and gingerly pulled it out onto the main. The Marias Pass Division is run by Centralized Train Control (CTC), with working signals throughout. Since my train had no switching to do, all I had to do was follow my train, watch the signals, and stop when they turned red. I was glad that I had studied up the week before for a Trains.com article on reading signal aspects.

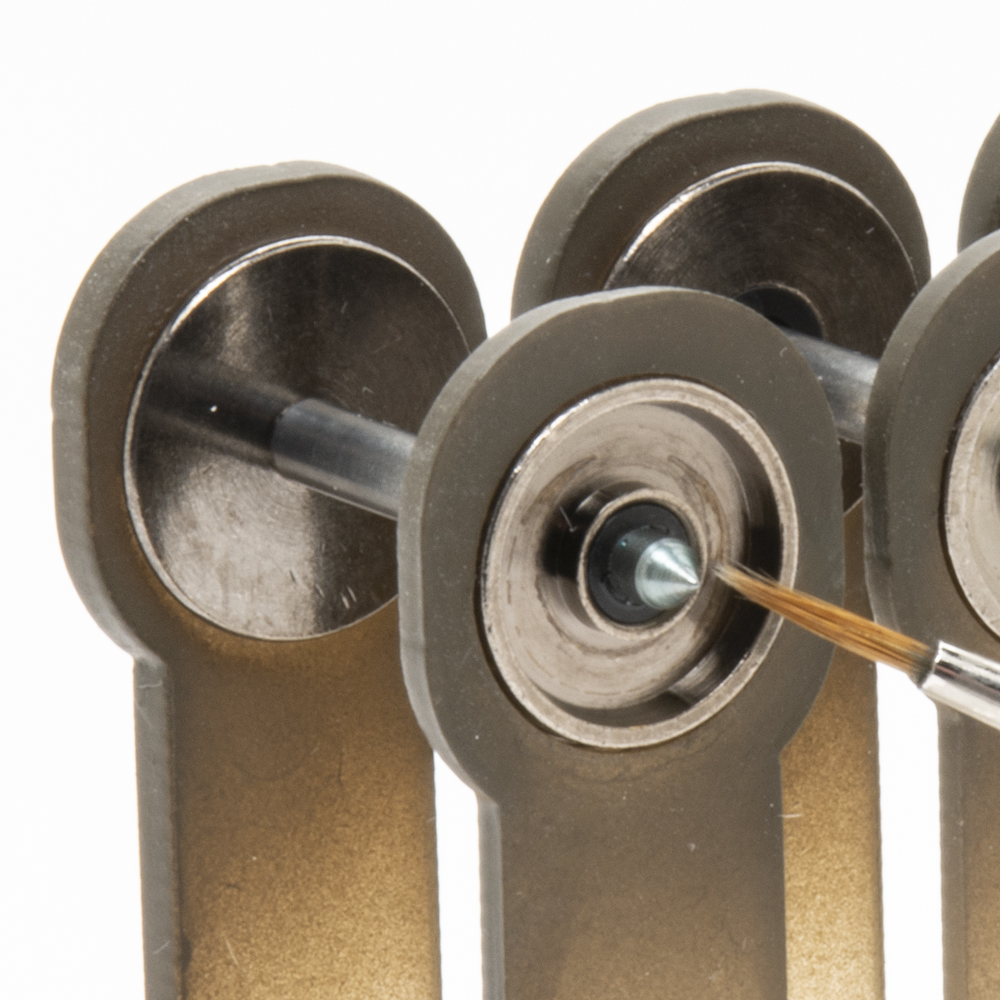

Model railroaders are familiar with a variation on Murphy’s Law: If something can go wrong, it will do so during an operating session. The first thing went wrong with my train while climbing the grade over Marias Pass. Joe was operating the helper locomotive tacked onto the rear of my train, and we got out of synch when trying to uncouple his locomotive just over the summit. A five-unit articulated spine car near the end of my train derailed. When Joe tried to put it back on the rails, it came apart in the middle. He found a small screw on the track – possibly the reason it derailed in the first place. But he couldn’t find where it might have come from, nor how it might have been used to reconnect the articulated units. I offered to take a look at the car, but when I turned it over, there was a snap – and suddenly one of the wheel platforms came off in my hand. Oops! Lesson 1: Let the maintenance department (that is, the layout owner) handle bad orders.

Another problem – not my fault this time, honest – sent me into a panic. Somehow my radio throttle (and several others’, as I found out) lost contact with the Digital Command Control system. My train was rolling toward a red signal at Summit, but there was no response to my frantic orders to stop. Luckily, I was moving slowly and I didn’t encounter any stopped trains ahead of me before control was restored. I backed up to the signal and waited for the green.

After passing through the yard at Cutbank on the upper level of the mushroom, I descended the helix to the middle deck. I waited and waited for it to re-emerge, only to eventually spot it on the other side of the aisle from me. Apparently, there was more than one way out of the multi-track helix, depending on which track you took into it. My train had emerged on the far side of the helix from the tunnel portal I was watching and transited a good 100 feet of main line before I saw it. Beginner’s luck was on my side again, as there had been no red signals or stopped trains on those rails. Lesson 2: Familiarize yourself with the track plan before setting out on your journey.

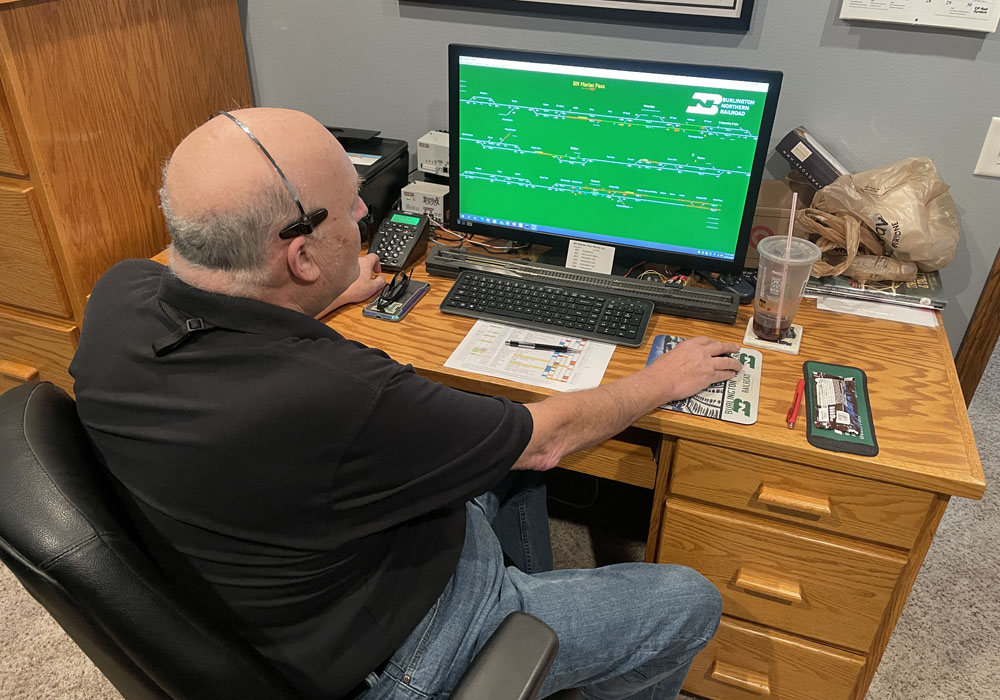

I shepherded my train around the rest of the layout and back into staging without incident, then retired to the crew lounge. I stopped into the dispatcher’s office to see how that job was performed. Bob Welke kindly demonstrated how the system, using the Computer Automated Traffic System (CATS) via the Java Model Railroad Interface (JMRI), worked. The green screen in front of him displayed a three-level schematic of the main line, its sidings and spurs, and the locations of trains. By clicking on track segments, Bob could clear routes for trains, line turnouts, and control signals.

Shortly, the trainmaster sought me out for another assignment: shepherding the Amtrak Empire Builder across the layout, in the opposite direction my first train had taken. “The good thing about this job is everybody has to get out of your way,” Joe told me. Nonetheless, the Builder spent a lot more time waiting at red signals than my first train had. A multi-train traffic jam in the helix backed up traffic for several blocks. While I was waiting, Rich, the yardmaster at Cutbank where I was waiting, used the fascia-mounted phone to call the dispatcher. “There’s a crossover here that keeps throwing under the Amtrak,” he said. “Though it’s normal again now.” A few minutes later, he picked up the phone again. “It’s doing it again,” he said. “But now it’s back to normal. It’s like every time I pick up the phone, it goes back.” Presently Alan arrived. The culprit was quickly located: an unlabeled red pushbutton on the chest-height fascia that controlled the crossover. When the dispatcher gave Rich local control of the Cutbank turnouts, that switch became active. He would bump into it when reaching across to uncouple cars from the Grain Grinder job he was switching, throwing the crossover. Lesson 3: Even experienced operators can make mistakes, especially on unfamiliar layouts. Lesson 3.5: Always label your layout controls!

My first operating session: Second stop, the UP

No, not the Union Pacific; rather, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which is home turf for this son of the Sault. After a delicious lunch courtesy of Alan and his wife, Darcy, we piled back into Rich’s SUV for the half-hour trip to Baraboo, Wis., and our second stop, Bob Welke’s HO scale Wisconsin & Upper Michigan. This sinuous, single-deck layout focuses on hauling ore from the mines of the UP to the docks of Lake Superior. I lucked out and drew a low number in the job lottery, again selecting a road job.

Traffic is controlled on Bob’s layout differently from Alan’s. Rather than trackside signals, engineers are issued track warrants that give their trains clearance to operate between designated stations. The dispatcher – Alan this time – kept track of train locations and arranged meets between those heading in opposite directions. Because of the large number of operators and the crowded aisles, Alan issued these authorizations verbally via two-way radio rather than writing out train orders.

“Amtrak 257 West to dispatch,” I called in.

“Dispatcher, go ahead Amtrak.”

“257, OS at Marquette.”

“Roger, Amtrak. Once train 41 passes, you are clear to Euclid.”

“257 out.”

I felt like a real railroader.

I regret that I didn’t have time to photograph this layout because I was kept so busy. I first ran the Amtrak Lake Superior Limited. A bad order car had to be removed from my consist early on, but other than that, the trip went smoothly. My next job didn’t, though. I assumed because the job sheet said “through freight,” that meant I didn’t have any switching to do. The first clue that I was wrong about that came when my train wouldn’t fit in the passing siding at Martins Landing, requiring a saw-by. My error wasn’t discovered until I was almost to Superior and dropped a sheaf of car cards on the floor. Bob helped me pick them up, and noting the color coding on four of them, pointed out that I was supposed to drop those cars at Marquette. Oops again. As it was, my train wouldn’t have fit in its designated staging track, either. Bob removed the four cars, and I pulled into staging, then slunk back to the crew lounge to lick my wounds. Lesson 4: Always read all the materials that come with your trains.

My last trip of the day was equally cursed. The job card for this freight said that the train was on track 3 in the double-ended staging yard. I pulled the car cards from slot 3 on the fascia, found what I thought was my train, lined the yard ladder for the main, and pulled out. Shortly I encountered a train coming at me the other way. I had taken the wrong train, headed the wrong direction. I had assumed that the card slot numbers corresponded to the staging track numbers – and then miscounted, taking the train on track 4 because it matched the car cards. My real train was still on track 3, but facing the other direction, and its car cards were in slot 7, just like it said farther down the job card. Lesson 4 had struck again.

My first operating session: One last bad order

By the time we emerged from Bob’s basement, the day had turned sunny and warm. Before we could get into Rich’s SUV, someone pointed out that the rear passenger-side tire was low. So the first stop of our voyage home was a gas station with an air pump. Luckily, when we stopped, the tire was in the right position for us to see that it wasn’t just low, but had a bolt sticking through the tread. Without a patch kit handy, there was no way we could just pump it back up and drive 2+ hours safely. Luckily, Rich had a full-sized spare. In a group effort that involved each of us crawling on our backs under the SUV at some point, we changed the tire, topped off the air pressure on all four wheels, and got back on the road.

Lesson 5: Meet the unexpected with good humor. “See, Steve, I told you you’d meet new people and make new friends,” Joe said.

“Sure, but you didn’t tell me we’d have shared adversity to bond over,” I replied.

We finally returned to our starting point in Milwaukee just 13 short hours after we’d started. After my first operating session, I was sore, tired, and hungry, and my hands were filthy from handling the tire. But I’d do it again in a heartbeat. If necessary, even the tire-changing part.

Hi, Steve

Nice Article. The Maria’s Pass layout is owned by Alan Schroeder, not Alex. We had another session recently in May. It was one of the best (busy and fun) sessions ever. I worked as one of the switchers at Whitefish Yard.

Marc Van Cleven