When we start out, we intend to make our dream come true. Our piqued imagination and the enthusiasm of fellow modelers are necessary to sustain us through the long construction process. Long-term and second-go-round railroad gardeners have used strong building materials for their walks, retaining walls, railroad and structures. They researched the plants to find appropriately hardy trees and groundcover. In this story we’ll share landscaping tips by visiting three gardens whose builders found a balance between the solid structure of the railway and their aesthetic dreams.

The two parts—the garden and the railway—coexist, marry, and sometimes multiply. Train people could learn about healthy gardens from the sustainable-landscape pros at http://www.loveyourlandscape.com/sustainability/landscape.cfm Granted, “sustainable” is an overused buzzword, so let’s think in terms of stability. What makes the physical layout long lasting? On the aesthetic side of the hobby, how can you plan a low-maintenance garden that will keep you interested in it?

Hard hardscape

You might not want the dinosaur theme in photo 1, but notice how well Jim and Bill Ralph’s stucco-and-paint cliff matches the real feather rock above. On top, they mirrored more stucco-rock outcroppings, which are colored to create the amusement-park-mining theme. The Ralph brothers combined forces to blend the fun look of Knott’s Berry Farm and other parks with the practicality of well-designed trackwork and easy plants.

In your railway, you could impregnate stucco cliffs with sharp stones to look like the mountain was blasted away for the railroad. Concrete mix and cement products are great for permanent, easy-care features. Get a flat-bottomed tub, cement colorant, dust masks, and instruction booklets at your local home-improvement store. In an afternoon, you could construct a mass of concrete by pushing it into wire mesh—a long lasting vertical wall affording more space for rails.

Most stable structure

I once attended a lecture on the “nature of the world” and discovered it’s all about triangles, which are nature’s strongest building units. When working in 3-D, as we do, it’s helpful to stabilize everything, and triangles are nature’s secret.

Rockwork. When stacking dry rocks into a wall, think of a three-legged stool, which never wobbles. Feel how secure each rock sits when three points of it rest on solid ground, preferably between two rocks, and leaning into the hill (dirt), the way a stool’s legs lean out. That’s why mountains are stable.

Buildings. Plastic-building joints, particularly roofs, need beefing up with “fillets” glued inside the joints. Unseen, these triangular lines of weatherproof glue (or glue and wood) mechanically prevent warping in the sun. Diagonal sticks, glued inside, brace walls from collapsing like an empty box, which is the least stable structure.

Bridges. Trestles and trusses are stable because they are formed of a series of triangles and are joined with other triangles. A triangle makes a good truss because it can’t deform without compressing or stretching any of the sides. Anchoring or weighing legs down at their bottoms (photo 2) enhances the triangle effect. Sharp gravel (triangular edges) could also help to anchor the legs.

Trees. When a little sun-loving conifer is trained to have a tapered apex, it looks more like a scale tree. The pointy top gives it an advantage—the sun has a better chance of reaching all the branches, as opposed to a flat-topped tree, where lower branches would be in shade.

Figures. Group deer, passengers, and even trees in irregular triangles, never exactly the same distance apart. Three, five, and other odd numbers create motion. Pose figures at an angle so they’re looking at something, instead of in a catatonic stare (straight ahead at us).Nails. In building with scale lumber, add strength to joints by driving in two nails at angles to each other. “Toe-nailing” is critical when shooting headless brads into a structure. A drop of glue in that joint will create the third leg of the triangle.

Evolution

A study called the Biology of Ageing has announced that our body parts age at different rates, depending on genetics and environment. We adapt. For Dan and Anita Brown, “doing their best” to stay active in the hobby meant building a raised railroad (photo 3). Their planter-box railroad has evolved with them. Still beautiful, the railway garden is less fussy, with fewer groundcovers and more decorative gravel mulch. Their dwarf trees require little care, especially after years of learning about each species. Later, it sometimes became a chore to get trains running if guests unexpectedly arrive, so they built benchwork, which gets them out of doors and focused on healthy activities instead (photo 4).

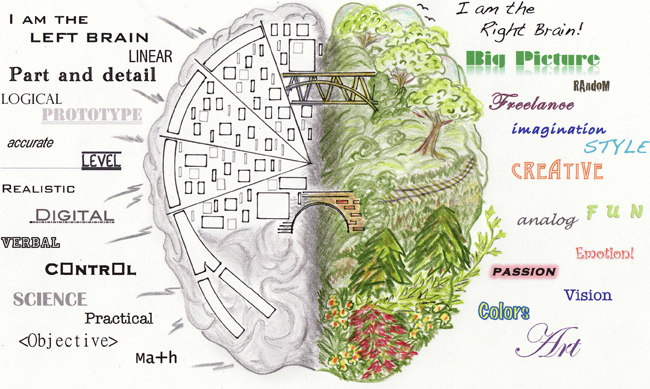

Did you know you can teach an old brain new tricks? Building something with two hands creates new neuron pathways. Get a kit if you’re new to model building. Get plans if you’re already a hand. Figure 1 shows how to understand, appreciate, and feed both sides of your brain for a more balanced, longer-lived railway, and possibly a healthier you.

Related reference

• See Peter Jones’ “A hard look at our individual futures” in the Aug. 2002 GR, p. 100.

Regional gardening reports

Zones listed are USDA Hardiness Zones

Question: How do you and fellow garden railroaders sustain your hobby or keep up your interest in maintaining it?

Chip Gierhart, Bay Area

Garden Railway Society

Palo Alto, California, Zone 9

I have seen a lot of garden railroads over 30 years. They come and go. The biggest unplanned item for owners is maintenance. We all love to build but our plans are often bigger than our time down the road. Few of us like raking, picking up, or cleaning up after animals.

Design your railway for maintenance. If you have leaves, plan to use a leaf blower. For my roadbed, I used 3/8″ crushed black basalt, which “locks” into place; other people have mixed cement or glue (concrete-bonding adhesive or Titebond II) into their fines. I glue a bent paper clip onto the bases of figures so they will survive the windstorm of the blower. For water features, I dug a 2′ x 2′ x 4′ hole, lined it with rubber, and filled it with milk crates (and pumps). It’s covered by screen with rounded 4-6″ rocks on top to keep out raccoons and allow me to easily blow away leaves. I clean it every two to three years.

Plant for the long term. Any groundcover with the word “creeping” in the name will remind you of the fact too often. If you want to get coverage quickly, you might space out a slow, steady grower, such as lemon thyme, but put in some woolly thyme to fill in for the short term.

Ray Turner, Bay Area GRS

San Jose, California, Zone 9

I’ve been in the hobby since 1992 and now enjoy camaraderie, mutual assistance, and friends to draw on to run operations on my railroad. As superintendent of the 10 districts in our large society, I help districts organize local activities but we invite everyone.

Learn at clinics. Our club hosts workshops on plants, pruning, rock casting, critter construction, and figure molding, which give members an opportunity to learn new skills from each other.

Richard Friedman, Sacramento Valley Garden Railway Society

Sacramento, California, Zone 9

Another guy and I decided not to build anything of our own at the critter clinic Ray Turner mentioned, but we worked together to help another modeler and now we’re friends and meet up at train shows. After getting some hands-on experience, I started my own critter.

Get track-cleaning help. My critter-build project started out as an MDC industrial switcher. I put two 9V batteries in it for a little longer running time—no change in speed, but longer running. I plan to pull a track-cleaning car behind it and may put another 9V battery pack in the track-cleaning car to get the pair around my line. I am having a little trouble with lighting and with mounting Kadee couplers on this thing. They seem to be too low or stick out way too far, but that’s the “enjoyment with everlasting challenge” part!

Keith Yundt, School of Hard Knocks

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, Zone 6B

Sustainability is one of those things you don’t immediately think about when you start off in this hobby but it certainly is something you learn about after you’ve been in it for a while—and that usually means learning the hard way.

Strategize. I try to do a little bit whenever I get the chance, so I don’t feel depressed and overwhelmed when I look out the window at my railroad after months of neglect. For example, in the cold and wet winter months, if the weather is good for a day or two, I try to spend a little time picking up wind-blown debris, weeding, and fixing damage from weather or animals, so that in the spring the cleanup isn’t as overwhelming. It’s amazing how much you can get done in half-hour bursts. My strategy for plants means lots of sedums and thymes, which are easy to keep in check.

Don’t overbuild. We all love expanding beyond a point that we can maintain. It’s better to start small, run a season or two, then expand a little, run a season or two, etc., until you reach a nice equilibrium. After all, the point is to run trains, not to spend all our time weeding—which reminds me of my last bit of advice: put a train on while you’re out there weeding!