Western Pacific Railroad history

John S. Ingles photo

The Western Pacific Railroad almost “had it all.” It ran passenger and freight trains, in mountain and desert scenery, behind vintage steam engines that survived World War II and hauled excursions, and then colorful diesels, from early green-and-yellow FTs through orange-and-silver Fs and Geeps to dark-green second-generation EMDs and GEs. It hosted the award-winning transcontinental luxury train, the California Zephyr. In the 1970s, it was led by well-known rail executive A. E. Perlman, and spiffed up its final four F units. It even owned an electric interurban, Sacramento Northern, which stretched 175 miles from San Francisco to Chico. Perhaps WP’s only missing element was a commuter service.

Surveyor Arthur W. Keddie had a dream: to build a railroad through Beckwourth Pass, lowest crossing of the Sierra Nevada at 5,003 feet, and maintain a maximum 1 percent grade through the canyons of the Feather River and Spanish Creek. He was laughed at by the Big Four (the men who backed the Central Pacific), who stuck with the Donner Pass route, 150 miles shorter but whose summit was 2,000 feet higher.

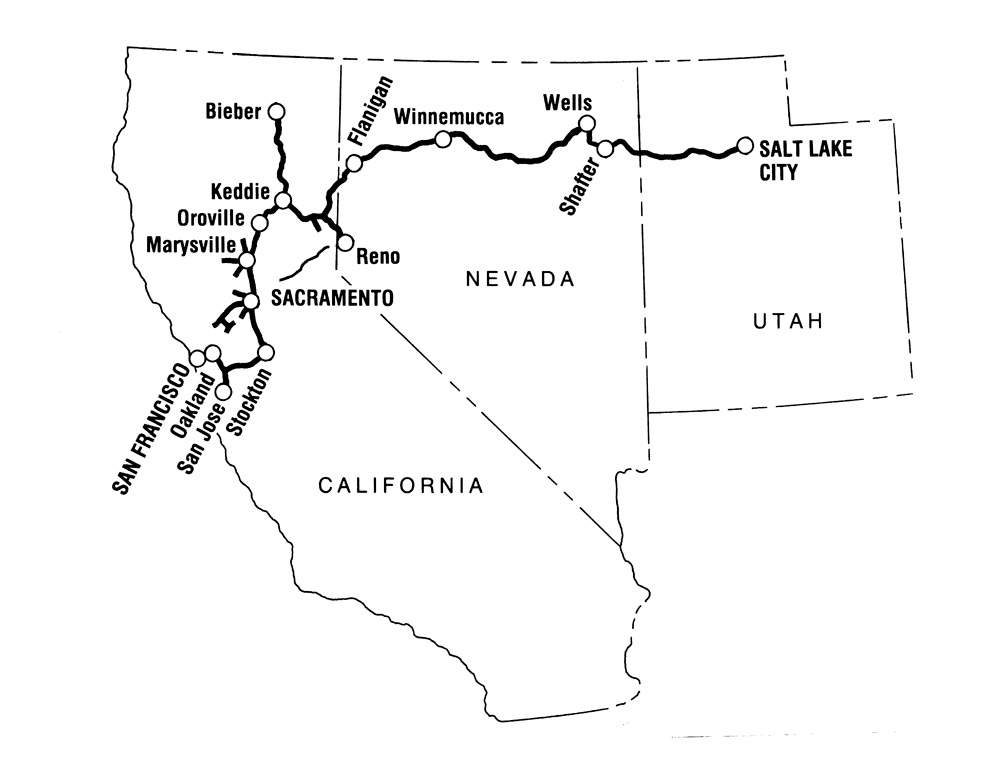

Keddie’s dream wouldn’t die, however, for on March 3, 1903, a group of investors signed a deed to build what would be the last transcontinental railroad, the Western Pacific Railroad, from Salt Lake City to San Francisco, using the engineering work done by Keddie. George Gould, owner of the Denver & Rio Grande and the Missouri Pacific, was the principal force behind the proposal. He pledged the D&RG as collateral, a move which put both the WP and the Rio Grande into receivership in 1916.

Building from east and west

Arthur L. Lloyd photo

Construction started in Salt Lake City. The line would be all 90-lb. rail and have no curve exceeding 10 degrees. To keep to the 1-percent maximum grade, the full-circle Williams Loop was built between Massack and Spring Garden, Calif., and another partial one, Arnold Loop, west of Wendover, Nev.

Work also went from Oakland eastward, and the last spike marking completion was driven on the bridge over Spanish Creek at Keddie, Calif., on Nov. 1, 1909. There was no ceremony. Section foreman Leonardo de Tomasso, age 25, did the honors with a standard steel pike. Arthur Keddie was still around, though. He rode WP’s first passenger train, and he spoke from the Plumas County Courthouse steps in Quincy, Calif., on Nov. 21, 1910.

WP was dispatched completely by train orders and timetable; its only block signals were on the paired track between Weso (Winnemucca) and Alazon (Wells) in Nevada, where eastbound WP and Southern Pacific trains used WP, while both roads’ westbounds used SP.

Western Pacific Railroad’s wartime transformation

World War II changed the complexion of the Western Pacific Railroad. It became an important carrier in its own right, no longer just settling for the leavings of giants Southern Pacific and Santa Fe. The diminutive Feather River Express, prior to the war made up of just a railway post office, baggage, coach, and sleeper, went to daytime operation to release its two tourist sleeping cars for military use. A 651-series parlor car replaced the sleeper, and you could ride in luxury between San Francisco (Oakland Pier) and Portola for $3 additional.

Trains 39 and 40 retained the name Exposition Flyer even though the Golden Gate International Exposition ended its run in 1940 (the train was numbered 39 and 40 for the two years of the fair). During the war, it often ran in two or more sections. I recall 40 arriving in Salt Lake once behind 4-8-2 No. 176 with 26 cars in tow, and no helper engine.

From the Presidio of Monterey, most military travel centered on SP, but I talked the transportation clerk into routing me WP when I went to basic training for World War II. By this time the War Production Board had allowed WP to install centralized traffic control between Oroville and Portola. After the war, WP installed centralized traffic control on all of its 924-mile main line except for the paired track in Nevada.

On March 20, 1949, WP passenger service leaped forward with the new Vista-Dome California Zephyr, operated with Chicago, Burlington & Quincy and the Denver & Rio Grande Western. Many an influential traffic manager rode the California Zephyr, and these men were impressed with the service offered by the three railroads. In 1951 WP landed a big Ford Motor assembly plant in Milpitas, Calif., on the San Jose line.

Working on the WP

Donald R. Kaplan photo

Along with other friends who went on to work on the Western Pacific Railroad, we rectified the lack of a “last spike” ceremony for WP’s completion by organizing the “Ruby Jubilee” at Keddie on November 1, 1949. Leonardo de Tomasso himself, by then age 65, again did the honors. The westbound California Zephyr paused behind him, while Virginia & Truckee locomotive 12 Genoa, loaned to WP by the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, stood on the wye leading to Bieber and blew its whistle.

The public relations department handled all WP special passenger trains, other than military trains. We took Budd’s demonstrator RDC1 over WP and its two subsidiaries, SN and Tidewater Southern. We operated double-headed steam with No. 94 and 2-8-2 No. 334, and we had some steel gondolas equipped with ladders for a trip on the Feather River Railway. WP management was sympathetic to our cause, and the railroad ran several successful trips.

Although WP was a great railroad to follow and to work for, clouds were on the horizon. The California Zephyr still ran full in peak periods, but was virtually empty east of Portola in winter. I left the railroad in 1961 and the California Zephyr made its last run on March 22, 1970 — only to resume years later under Amtrak.

Western Pacific stayed independent until acquired by Union Pacific in 1982, but it still lives.

Great article by Art Lloyd, a legend in California passenger railroading.