I don’t keep bucket lists, but one thing I’d been hoping to visit one day was the famed Oyster Bar, the historic restaurant that’s been operating in the catacombs of New York City’s Grand Central Terminal nearly continuously for 110 years. I finally got my chance a couple of weeks ago during a short research trip to Manhattan.

The Oyster Bar is worth trying for any number of reasons. For one thing, it’s a terrific restaurant, especially if you like seafood. And oysters of course, raw or cooked. For another, it’s a legendary restaurant on the New York scene, as famous in its own way as Sardi’s or Katz’s Delicatessen. Most of all for me, literally a card-carrying New York Central fan (member No. 7239 in the NYCSHS, thank you very much), the Oyster Bar is a reminder of the greatness of the Water Level Route.

Not that the NYC had direct involvement in the operation of the Oyster Bar, but the fact is the railroad’s architects — Reed & Stem and, supplementally, Warren & Wetmore — provided for the restaurant space, and generously so. No wonder generations of New Yorkers and travelers have fallen in love with the place. I daresay it’s as revered as that icon of the GCT concourse, the Information Booth.

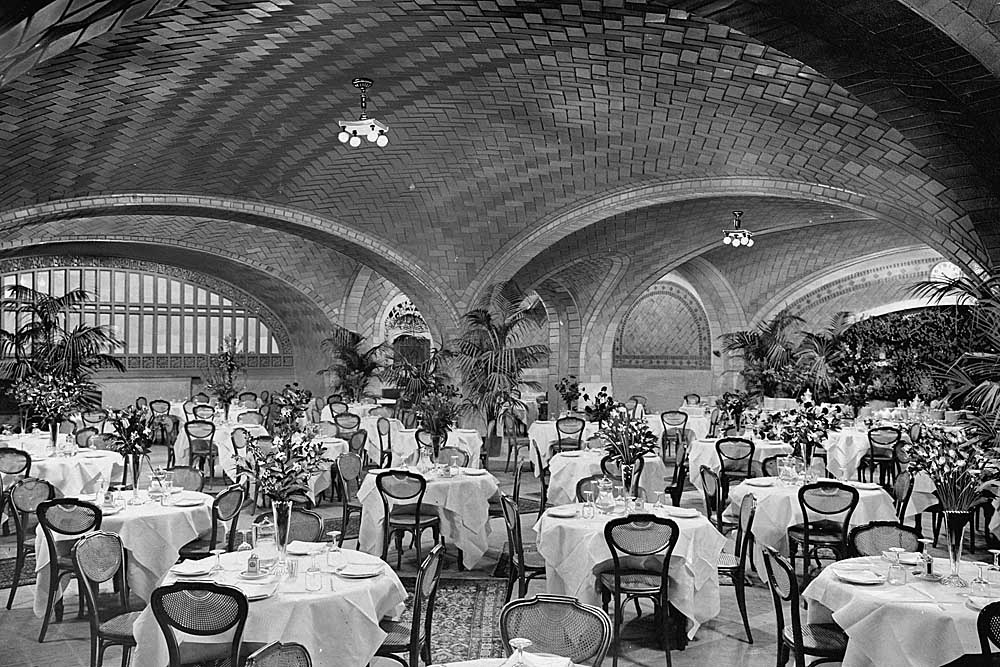

Over the years, the Oyster Bar has seen small changes in menus, in ownership, and in décor. When it first opened, the linen tablecloths, sparkling glassware, and palm fronds were signs of a first-class eatery. Things are more casual now, with tables covered in red-and-white checkered oilcloth. But the essence of the restaurant is the same.

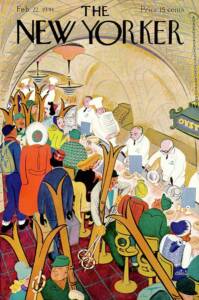

First known as the Grand Central Terminal Restaurant, at some point later it received its more famous name. The Oyster Bar gradually became part of New York lore. Celebrities frequented its bar, untold millions of travelers grabbed a bite to eat before grabbing a train for Poughkeepsie or Cincinnati, and, as if to officially sanctify the place, The New Yorkermagazine hired an artist to depict the restaurant for the Feb. 22, 1941, cover, featuring a lot of skiers obviously ticketed for NYC’s next train to Lake Placid.

The magazine still loved the restaurant some 77 years later when writer Oli Coleman extolled its virtues in a 2018 piece in The New Yorker’s Annals of Gastronomy. “The Oyster Bar has always been a good place for visitors to get an idea of the city,” Coleman wrote. “It’s fast. It’s loud. It’s abrupt. It’s big — two large dining rooms, a lounge, and a series of low lunch counters — yet it’s a crush: by the time you have hinged and folded into a seat at the counter, you will almost certainly have pressed your body against the body of your neighbor, who is a stranger and will likely remain so, although you will soon know his or her business. The space, like Grand Central as a whole, is ingeniously simple yet gorgeous, impatiently glamorous.”

I allowed myself to feel slightly glamorous as I met my dinner companion on a recent Thursday evening. Waiting for me was my friend Dennis Livesey, the noted photographer and author and bona fide New Yorker. Dennis is known for his dramatic images of contemporary steam, and his depictions of railroading around Manhattan — both transit and heavy rail — are nonpareil. That’s especially true for his photographs of Grand Central, one of his frequent muses.

I arrived a bit past the peak dinner hour, but the huge dining room and its long raw bar were still mostly full and buzzing. After studying the impossibly big menu for a while — it’s hard to imagine any kind of seafood that isn’t offered — we both settled on pan-fried trout, a pair of generous filets, prepared perfectly.

Then I took in a moment to study the surroundings. The Oyster Bar, like GCT itself, gives you a wonderful sense of place, a feeling you’re really arrived. Some of that is due to the attentive, uniformed staff. But what really gets your attention is the spectacular ceiling, actually a series of vaulted arches clad in the Gustavino tile system, which uses interlocking terracotta tiles as beautiful as they are functional. The ceiling looks the same as it did when the restaurant welcomed special guests on Feb. 1, 1913 — a day before the rest of the terminal opened.

Our dinner gave Dennis and I a chance to talk about how much we both love GCT. I’ve been to Grand Central countless times over the years, usually just to walk through it but occasionally to catch a Metro-North train. On one lucky evening in 1977, I even caught a roomette on Amtrak No. 49, the Lake Shore Limited, back when GCT still was an intercity station.

But I’m a piker compared with Livesey, a Manhattan resident whose bond with Grand Central is especially close. After dinner he gave me an excellent tour of the place. We reveled in the vast spaces, the rhythm of hurried steps on the marble, and the echoed murmur of hundreds of voices. Dennis has just the right words for the feeling.

“When you arrive at Grand Central, you know you have arrived at a great metropolis,” he told me later. “But further than that, while you know you are in an important city, the building makes YOU important. You can start your time in New York with drive and purpose. Nothing can stop you or your dreams.”

That’s the perfect word, Dennis: dreams. Later that evening, as the crowds thinned and we made our way over to the west end of the concourse to Track 34, where the Century customarily departed, I imagined a similar evening 70 years ago. The terminal is getting quiet and I’m waiting to board train 59, the Chicagoan, the 10:10 p.m. departure for Detroit. The fact the dining car will be closed for the evening doesn’t matter: I ate at the Oyster Bar.