Roger Carp originally wrote this fabulous introduction to display layouts for our special issue, Display Layouts & Showrooms. Unfortunately, we didn’t have space to include it, but we’re sharing the complete article here for your enjoyment. If you missed that issue, you can still order your copy. — Ed.

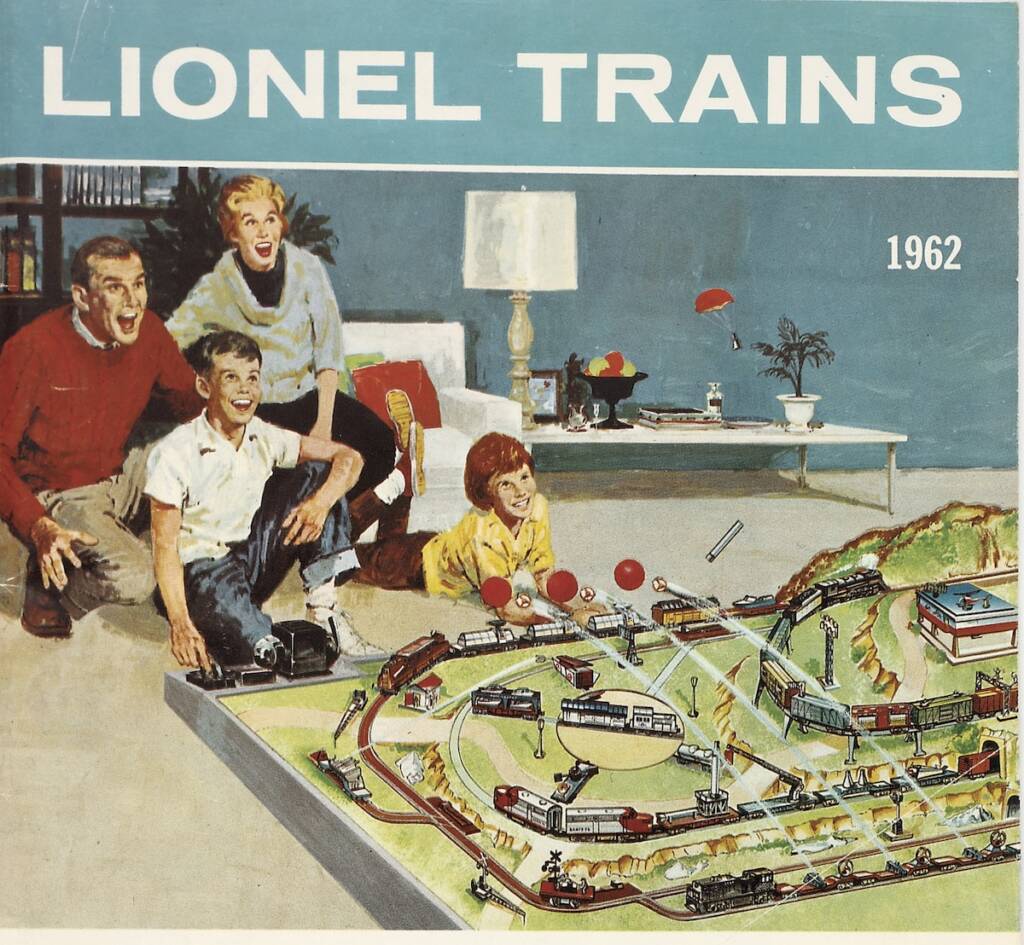

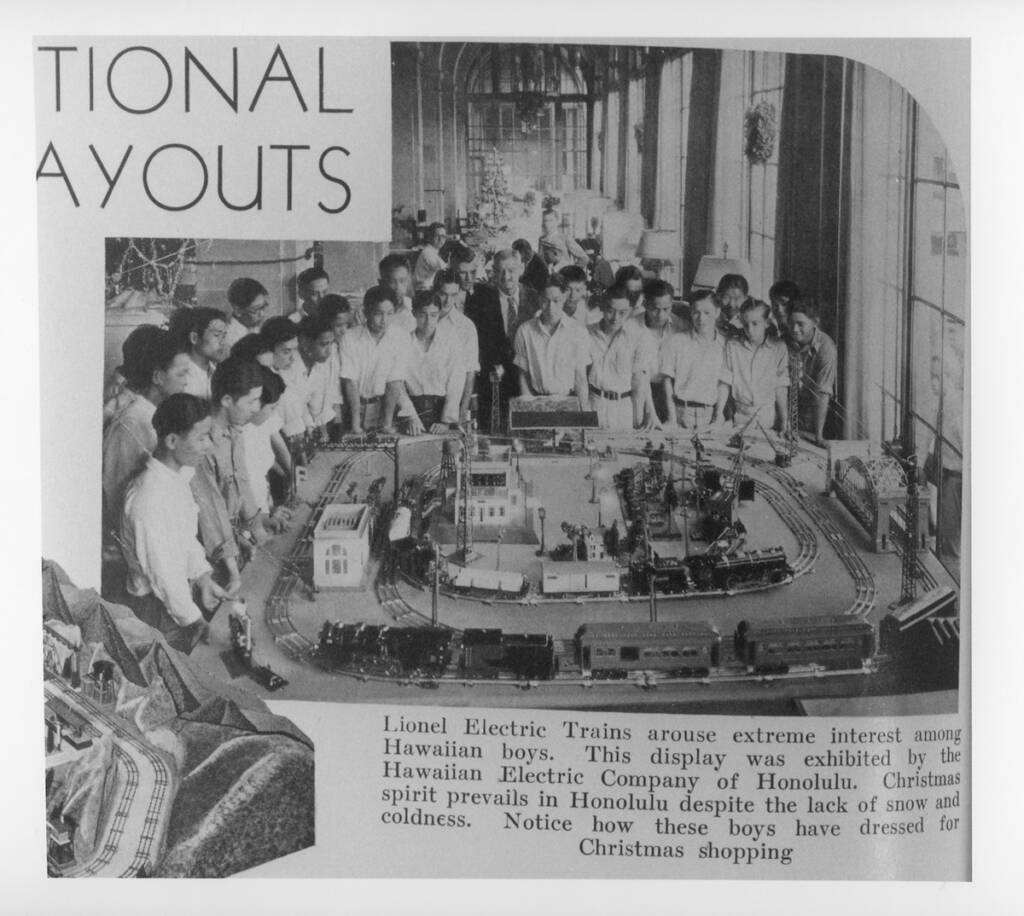

Executives at the Lionel Corp. and the A.C. Gilbert Co. realized that promoting their O and S gauge locomotives, rolling stock, and accessories required something beyond clever words and colorful artwork and photos. More important was presenting those trains in action. Kids and adults needed to see everything perform, regardless of whether doing so meant witnessing live demonstrations via displays or viewing commercial movies and promotional films or television programs and advertisements.

Action and movement were essential because they conveyed the magic behind toy trains. What was this magic? Simply that the terrific playthings from Lionel and Gilbert depended on electricity — household current — to race forward and back, to flash their lights, blast their horns and whistles, dump coal and little barrels, and a great deal more.

No mystery surrounded what was happening — viewers were aware the trains and accessories were powered by electricity. Still, the effect was magical and miraculous, as the toy trains were given life by a force no one could see. Electric current might be felt in the form of a mild shock or heard as crackles, pops, and buzzes. Actually seeing electrons bounce around crazily was a skill only Superman possessed. Yet the impact of electricity could be detected by even a young child. Electrical effects were miracles to be witnessed.

Which assuredly was the reason that A.C. Gilbert, who practiced tricks of magic, and his peer and competitor, Joshua Lionel Cowen, believed the popularity of their little electric trains related to the magic those playthings performed. Precisely because electric trains didn’t need to be manipulated directly by touch. Far from it! An invisible force controlled them and made them change in ways that left audiences amazed and amused.

Importance of displays

The operating layouts and countertop displays Lionel and Gilbert developed and marketed during the postwar decades reflected this underlying assumption that consumers longed to be entertained and awed by the miraculous effects electricity could create. The best method for toy trains to meet the expectations and hopes of consumers was to make it possible for anyone to watch engines race and signals flash, to hear motors grind and whistles roar, and even to smell the smoke puffing out of the blackened smokestacks.

Those different sensations would leave audiences enchanted. They would cast a spell potent enough to compel children to plead to take an electric train home and potent enough to compel adults to spend whatever it took to make their children’s wishes come true. For every generation, the magic of an electric train had to become theirs to replicate.

Expressing and presenting the magic of electric trains and accessories grew in importance during the postwar era. Display makers, sales personnel, and photographers recognized how vital it was to convey the magic and beauty of Lionel and Gilbert toys.

Those creative individuals discovered a host of techniques for accomplishing their goals. Some designed operating displays for retail outlets. Others exploited mass media to publicize the excitement of toy trains. Still others developed showrooms and sales offices where the public and the trade watched demonstrations of models. In accomplishing those tasks, the individuals earning our respect lifted sales and transformed sophisticated electric playthings into symbols of how life kept on improving in modern America.

Displays first

Where should we begin? How about around the turn of the 20th century, a little more than a decade before A.C. Gilbert cast aside a career as a medical doctor to make and market magic kits and the construction toys known as Erector Sets. A slightly older fellow named Joshua Lionel Cohen was selling what amounted to displays. He offered merchants in New York miniature railcars that used batteries to power their rudimentary motors so they could move around loops of track while showing off consumer goods. The goal was to entice pedestrians to walk inside to purchase whatever was being displayed.

To Cohen’s surprise and delight, however, people proved to be more interested in bringing home one of his motorized models than in buying whatever it was promoting. A noteworthy lesson was learned by Cohen: The action and magic created by a moving toy train could drive adults and children to ask for his products and spend money on them.

The Lionel Manufacturing Co., as Cohen and his business partner, Harry Grant, named their enterprise, pressed ahead. It developed and sold a growing line of motorized miniature locomotives and trolleys, along with models of passenger and freight cars for the engines to pull over the sections of track Lionel produced. Then customers were able to create displays of their own at home that incorporated the stations, signals, and other so-called accessories Lionel made in its own shops and factory or acquired elsewhere.

Perhaps the next significant step forward for Lionel was the establishment in the 1910s of a specialized department at its manufacturing facility expressly for constructing large displays for department stores and other commercial sites to purchase. Displays in retail establishments would ensure that larger groups were seeing Lionel trains in action. Men with an expertise in carpentry, electricity, and cabinetry were hired by Lionel to handle the tasks related to designing and constructing displays for various accounts.

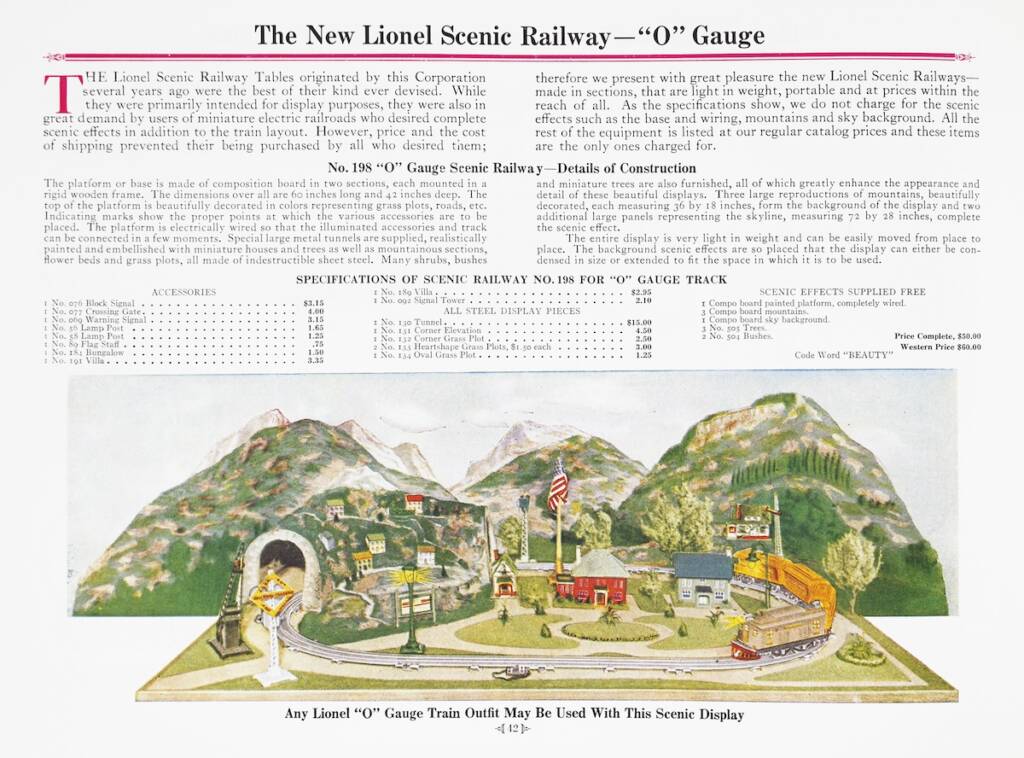

A decade later, executives at Lionel concluded that private individuals should be tempted to buy their own compact and landscaped operating displays. Out came Lionel Scenic Railways. Individuals affiliated with the Display Department now added to their roles responsibility for finishing the Standard and O gauge scenic items, so beautifully depicted and described in Lionel’s full-color consumer catalogs beginning with 1922.

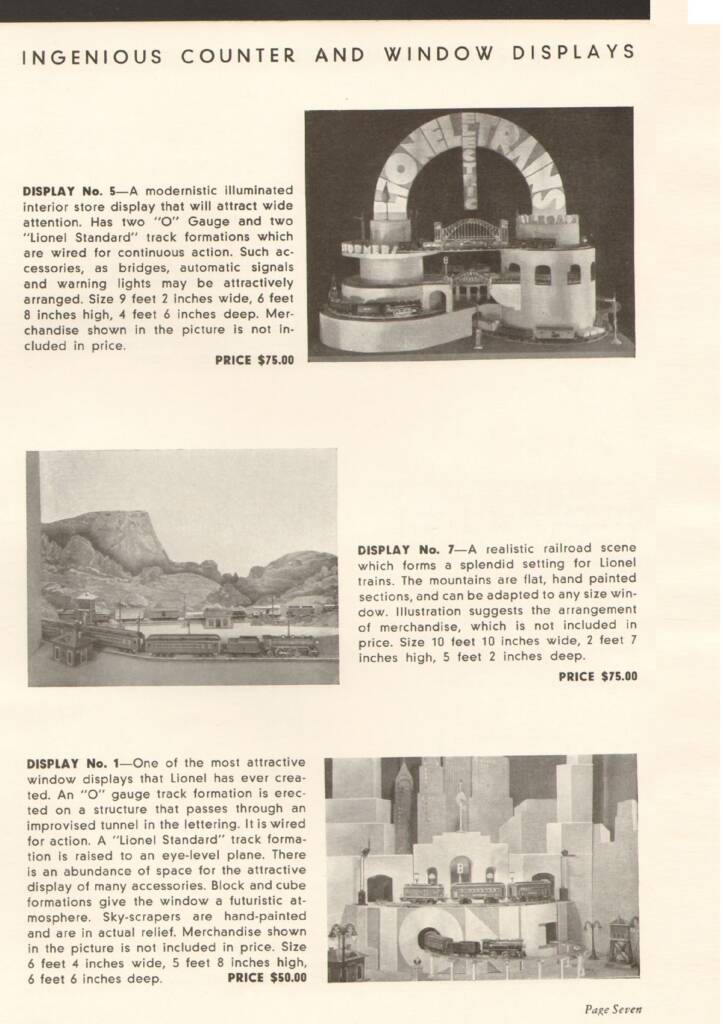

Still later during the 1930s, after shifting away from Lionel Scenic Railways, the skilled artisans in charge of designing and building displays turned their attention almost exclusively toward retail accounts. Promotional catalogs showed potential customers the host of signs, lights, countertop displays, and even operating items that could be bought with the intention of helping merchants publicize the Lionel trains they intended to sell.

Prewar marvels

Two principal points need to be set forth when discussing the displays the Lionel Corp. made available during the final two decades of the pre-World War II period.

First, those displays were marvels of design, construction, and animation. The talented individuals working with Joseph Donato Sr. at the Lionel factory in northern New Jersey brilliantly shaped and formed wood and metal to present individual models and outfits. They capitalized on what they learned about electric lighting and the creation of shadows to enhance the drama and excitement associated with the company’s finest Standard and O gauge trains and accessories. Those magical toys never looked better.

A number of those marvels from the 1920s and 1930s were highlighted in a previous special-interest publication, Lionel Trains: Best Layouts & Store Displays. Readers might remember the information shared there about the Lionel Scenic Railways, along with the illustrations reproduced to show in all their glory countertop displays characterized by sleek, almost streamlined lettering and captivating artwork depicting railroad themes and personnel. They brought to life what we love about Art Deco trends.

Also entertaining viewers 90 years ago and collectors today were different store displays used to herald Lionel’s connection with Walt Disney Studios. Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck dominated some countertop items that pleased consumers thanks to their moving parts. And we can’t forget the murals, electric clocks, and neon signs that Lionel ordered from outside firms. Dealers were invited to purchase those eye-catching pieces to validate their ties with Lionel to a public eager to bring home the latest O-27 and O gauge sets, which often were lined up on familiar, white-painted shelf displays.

Sounds fascinating, doesn’t it? Sadly, however, a second point about prewar items comes into play here. Specifically, that few of them have survived to permit firsthand appreciation. Only a handful of Lionel Scenic Railways can be seen a century after they were constructed. The same is true of Disney memorabilia fabricated during the Great Depression, along with the popular countertop rows of simple shelves assembled for merchants everywhere. Our sole recourse is to feel gratitude for the pieces still around and the collectors, including Stephen Blotner and Russ MacNair, willing to share them.

Centralized showrooms

Also lost to the ages are the showrooms Lionel and the A.C. Gilbert Co. set up to impress members of the toy trade and the general public with their latest products. Both of those grand businesses established elaborate showrooms in metropolitan areas to make it possible for wholesale and retail accounts to view their trains and accessories in action. Again, leading executives subscribing to the notion that displays were essential to their financial success hardly hesitated before taking the next step. They would announce a central location where their trains and related products could be demonstrated on a larger scale in an environment they and their sales teams could design, build, light, and own.

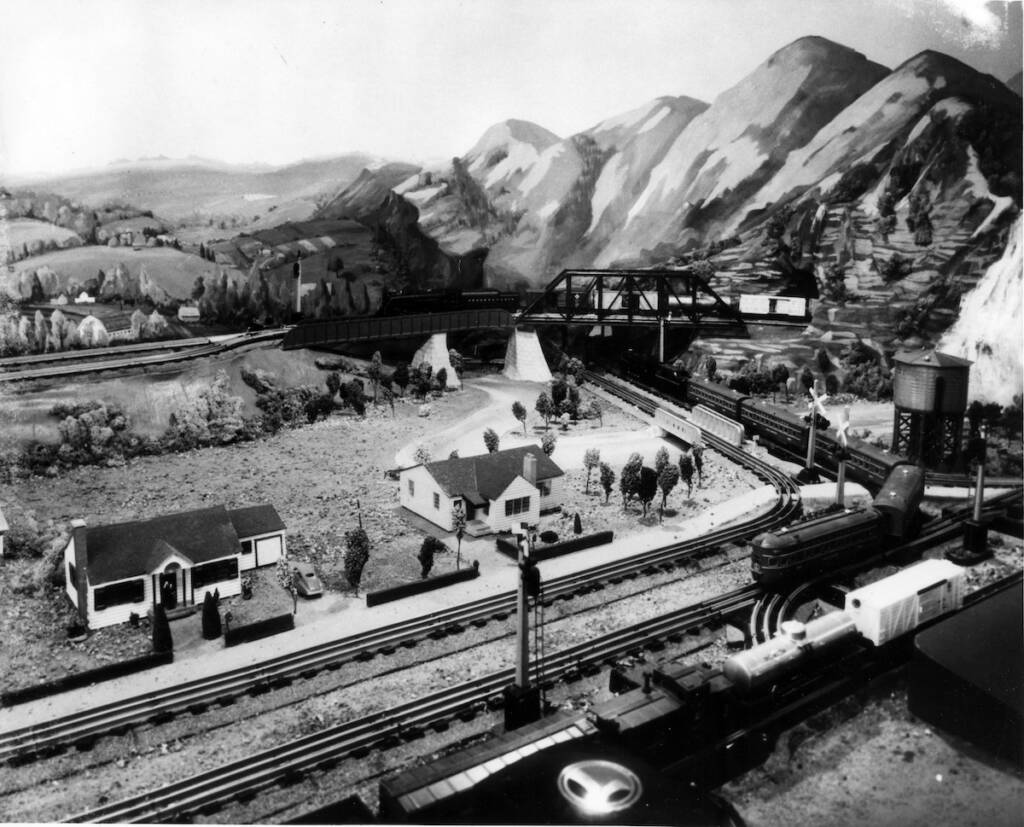

Inside showrooms, sales representatives and department store buyers watched with glee as brand-new locomotives pulled freight and passenger sets on layouts filled with riveting scenic effects. Colorful trains dashed across bridges and ducked in and out of tunnels. They climbed steep grades, flew forward, and roared down to the main level again. Meanwhile, trained employees were asked to fire up the operating freight loaders, signals, light towers, stations, and other ancillary objects Gilbert and Lionel depended on to fill out their lines and please consumers. Those novel accessories attested to the ingenuity of the engineering and model-making crews affiliated with the two toy train enterprises.

The importance of showrooms rose after organized events where domestic and foreign manufacturers of playthings exhibited their wares began to be held in New York City at the end of every winter. The multiple-day event in the nation’s biggest city took off in popularity in the 1900s. Except for the years during World War I and at the height of the Great Depression, what was known as the American Toy Fair never lost its status.

Lionel and then Gilbert

Joshua Cowen, always several steps ahead of his competitors, did much more than spearhead the development of the fair. Unlike the majority of his rivals, who were content to present their toys in rooms and suites rented on the floors of office structures on Fifth Avenue, he insisted that Lionel open its own showroom in midtown Manhattan. The firm leased more impressive quarters during the prewar era, with executives maintaining their offices next to Standard and O gauge layouts unparalleled in size and complexity. Also at Lionel’s exclusive headquarters at 48-52 East 21st Street and later 15 East 26th Street were erected simpler displays consisting of cataloged sets and new structures and accessories.

The Gilbert Co. staked a claim in New York City not long after it entered the toy train sweepstakes with its acquisition in 1938 of the assets and inventory of the American Flyer Manufacturing Co. of Chicago. It took possession of a multiple-floor building located where Broadway intersects with Fifth Avenue (not far from Lionel’s main office).

The official opening of what became known around the world as the Gilbert Hall of Science occurred in September of 1941. Children and grown-ups mingled with veterans of the toy industry to gaze in wonder at handsome displays of American Flyer O gauge trains. Nearby, they saw other Gilbert products, such as Erector Sets, woodworking tools, household appliances, chemistry outfits, juvenile puzzles, and Mysto-Magic kits.

Regional offices

Already, Lionel had vaulted ahead of other toy train firms by establishing regional showrooms in Chicago and San Francisco to take care of its accounts in the Midwest and along the Pacific Coast and in the Rocky Mountain states, respectively. Smaller displays than those erected in New York City distinguished those showrooms, which tended to limit visitors to men and women affiliated with authorized Lionel dealers and businesses.

The fact that Lionel limited access to its two regional showrooms has meant little information about them exists. To be sure, articles and photographs related to the sites in Chicago and San Francisco occasionally appeared in toy industry periodicals, notably Playthings and Toys & Novelties, or in publications from Lionel. Other than consulting those primary sources and reading interviews with former employees conducted years after the showrooms closed in the 1960s, no other avenues existed for toy train historians to learn what happened there. Essays about the personnel and displays at Lionel’s Chicago and San Francisco offices add to the value of this special-interest publication.

The same unfortunate point about a dearth of information and pictures applies to the Gilbert Halls of Science the company helped set up and supervise in Chicago, Miami, and Washington, D.C. Occasional mentions of the regional showrooms appeared in trade journals and inhouse publications for Gilbert’s employees and dealers. Otherwise, the smaller versions of the famous Hall of Science in New York City remain mysteries.

The Hall of Science located in Washington received the most attention, so you’ll find it profiled in Great Display Layouts and Showrooms. A few photographs about the Chicago Hall of Science do exist. The one in Florida, sadly, never earned much notice. Evidently, it was less a corporate showroom than an extension of a retail establishment owned and operated by Leroy Jahn, a friend of A.C. Gilbert, to sell trains and other toys.

Glory days

After writing paragraphs of despair about the lost treasures of the prewar era and the lack of pictures and stories about the regional showrooms, it feels great to share the good news that when it comes to the astonishing and thrilling world of operating displays from the 1950s and early 1960s there is plenty more to show and tell. The glorious times when electric trains and accessories were at the top of every boy’s holiday gift wish list are wonderfully documented and recollected. We have lots to share in the coming pages.

Catalogs put out by Lionel and Gilbert on an annual basis showed in terrific detail what designers of O and S gauge operating displays had to offer dealers big and small. We can usually supplement the descriptions and pictures printed there with instruction sheets and wiring diagrams. As a result, ambitious hobbyists will be able to make their own versions of several of the Lionel and American Flyer layouts highlighted here.

In other cases, we can provide sharp and detailed photos of surviving examples of memorable displays. Stephen Blotner, Daniel Brown, Ed Dougherty, Walt Downer, Russ MacNair, and Dennis Wittmann submitted images of their favorites from postwar days. Bob Horton, an expert on Lionel’s disparate promotional items, gave insights into the No. D-63 from 1952, the O gauge layout pictured on the cover of Great Display Layouts and Showrooms, that by consensus earns acclaim as the finest of Lionel’s postwar displays.

What the various essays and photographs prove time and again is how creative display specialists at Gilbert and Lionel were when asked to come up regularly with operating layouts varying in dimension and cost for retailers. The individuals designing the S or O gauge railroads measuring 4 x 6 feet, 4 x 8 feet, or 5 x 9 feet just knew from instinct and experience how to blend networks of track with areas for accessories in a perfectly balanced manner. The displays seldom felt cramped or barren. To the contrary, they allowed new sets to star while encouraging accessories to take on supporting roles.

In other words, shoppers had plenty to watch without feeling as though they had missed something. They might look initially at the locomotives pulling strings of freight cars or a passenger express over trestles and into mountain tunnels before wanting to investigate the gates and flashers protecting grade crossings. Next, viewers would take some long looks at the innovative light towers, freight-handling structures, and stations.

Department stores

A survey of operating O and S gauge displays from the postwar era must include items beyond the usual scope of what Lionel and Gilbert offered to retail accounts. Those exciting layouts launched hopes and nurtured dreams in the minds of the kids who saw them. There were, however, other kinds of displays manufacturers used to communicate directly and indirectly to audiences the advantages of owning one of their magical toy trains and supplementing it with accessories year after year at birthdays and holidays.

Consider, to begin, the operating model railroads constructed for the storefront windows of department stores or special areas in their toy sections. Generally speaking, crews of talented artisans on the payroll of those retail giants handled all the work of creating and maintaining their displays of Lionel and American Flyer trains. Tragically, virtually none of the individuals received ample credit and few photographs survived.

Sometimes, it must be noted, the craftsmen constructing and wiring operating layouts for department stores had been dispatched from the manufacturer. People at Lionel or Gilbert hit the road in the weeks before Christmas to assemble impressive displays or at the very least to update older ones and possibly monitor their operation.

Marketing people employed by the major producers of electric trains sought to record what they and their teams accomplished, which meant photos were taken and filed away. At the Gilbert Co., the highly respected Maury Romer supervised the development of the annual lineup of American Flyer trains while influencing how they were promoted. He salvaged pictures of displays in department stores, trade shows, and public events.

Dedicated collectors who knew Maury lovingly preserved his files; that’s how American Flyer experts David Garrigues and Ray Mohrlang managed to pass along the rare photographs currently available for us to study at www.americanflyerdisplays.org. Thanks to the generosity of curators Lonny Beno and Dale Smith, a selection of those nostalgic and cherished images can be shown in Great Display Layouts and Showrooms.

Dioramas and exhibits

The Advertising Department at Lionel adopted a different approach to promoting its electric trains after World War II. Under the leadership of Joseph Hanson and Banning Repplier, it aimed to capitalize on the novel and still barely tested medium of television. Movement, of course, was paramount for the simple reason that camera crews filming the live programs could show a train set in motion or let the host demonstrate how a freight loader really worked. Compact, action-packed layouts were thus required for TV shows.

Hanson, based at Lionel’s headquarters in New York City, realized that many of the programs were being broadcast by national television networks whose studios were just blocks away from his office. He decided Lionel must be able to build layouts and dioramas on short notice to fulfill the demands of TV personalities and producers. An agreement was hammered out with a tiny agency to hire a few artists to create and on occasion operate whatever Lionel needed. And so was born in 1948 Diorama Studios.

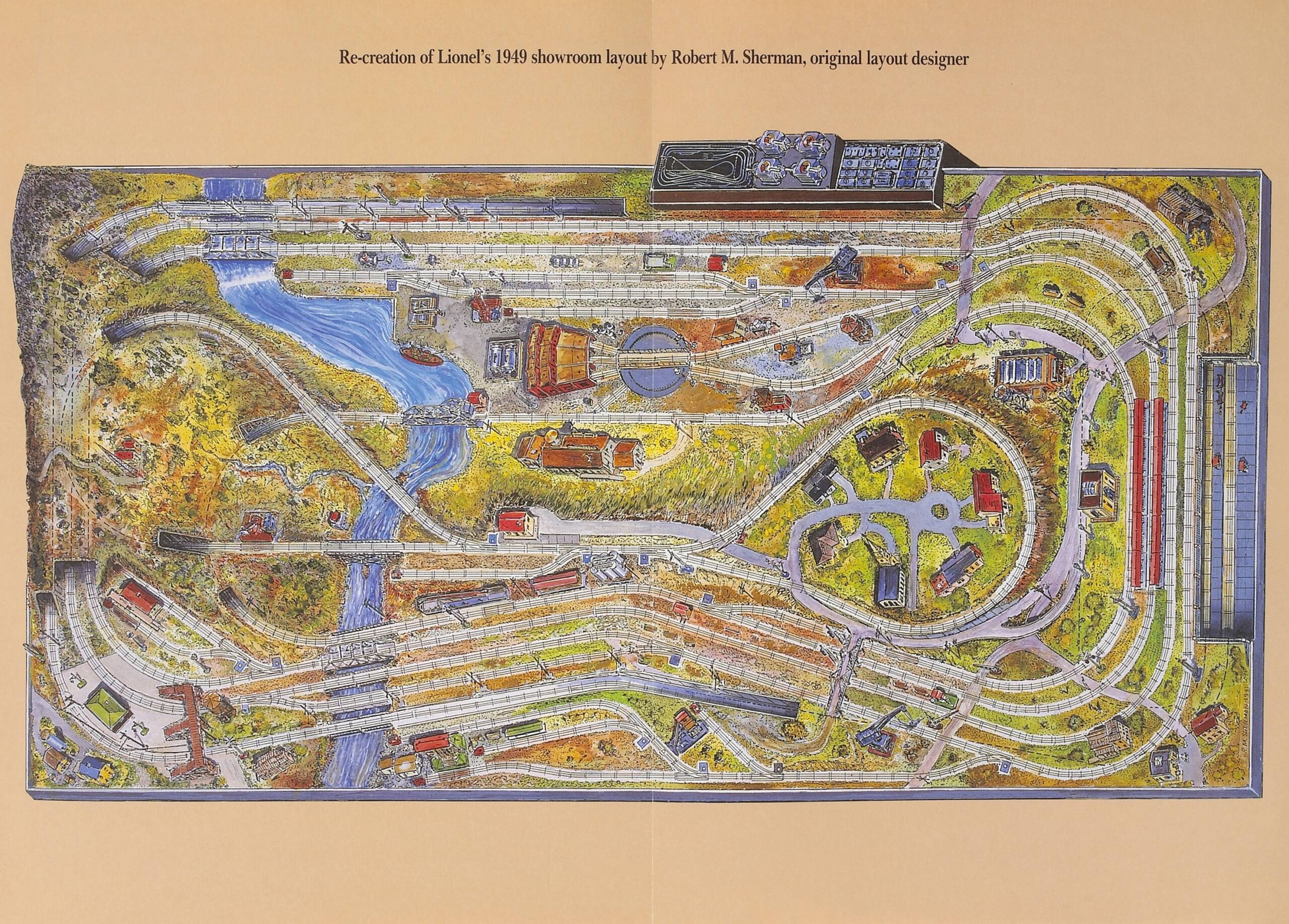

The great history of Diorama Studios has been told more than once in the pages of Classic Toy Trains and its special-issue publications. The legacy of the extraordinary trio toiling in the crowded workshop of Diorama Studios at 148 West Fourth Street — Robert Sherman, William Vollheim, and Arthur Zirul —must not be forgotten. They contributed in significant ways to the layout constructed for the Lionel showroom in 1949; the four O gauge railroads sponsored by the Police Athletic League in Rochester, New York, a year later; and displays for civic events, trade shows, television programs, a Broadway musical, and celebrities including Jackie Gleason, Arthur Godfrey, and Gypsy Rose Lee.

Besides showcasing some of the full-color photographs Bill Vollheim snapped in 1950 and 1951 of dioramas Bob Sherman and Art Zirul put together to herald the latest additions to the cataloged line, we plan to look in depth at a special layout they developed to publicize the benefits of Magne-Traction. That feature, pioneered by Chief Engineer Joseph Bonanno, enabled Lionel locomotives to ascend steeper grades, hang tightly to the rails at faster speeds, and pull more pieces of rolling stock. It revolutionized toy trains.

Time for fun

Discovering the wonders of historic Lionel and American Flyer operating layouts and getting insights into how to build your own versions. Learning more about forgotten displays in the legendary corporate showrooms maintained by the A.C. Gilbert Co. and the Lionel Corp. in New York City during the postwar decades. Going behind the scenes at the regional offices those businesses established in other parts of the country. These are only a few of the highlights waiting for you in Great Display Layouts and Showrooms.

You’ll also appreciate the Lionel exhibits at the World’s Fair held in New York in 1939-40 and the display layout from the middle of the 1950s you can still see in action in upstate New York. You won’t want to skip the story of Art Truman, who built three-rail layouts for Hollywood studios, celebrities in southern California, and trade exhibits. Nor will anyone think twice about flipping past the rare photos showing two young members of different royal families discovering electric toy trains. And then savor the photographs hobbyist Phillip Collins snapped to highlight his layout and its postwar Lionel murals.

Take your time to savor each article and investigate every photograph included in the pages to follow. Then be sure to stop every once in a while to express gratitude to the artists, designers, carpenters, electricians, and others who built these displays and created the operating layouts that garnered fame and fortune for Lionel and Gilbert and helped in countless ways to make collecting and operating electric trains such a fantastic hobby.