Anyone who lived through the late 1960s and cared about railroading knew that the future of the intercity passenger train was bleak, so long as it was in the hands of private companies mostly interested in exclusively hauling freight. After more than a decade’s worth of relentless abandonment and downgrading of service, it seemed only some sort of savior could save the day.

The passenger train found that savior in Anthony (Tony) Haswell, founder of the National Association of Railroad Passengers (NARP), relentless champion of public access to rail transportation, and persistent gadfly to Class I railroads. He was to railroads what Ralph Nader was to the automobile industry.

Haswell died Friday, May 17, in Tucson, Ariz., where he had retired many years ago. He was 93, according to information Haswell provided to Trains in 1975, although most reports are listing his age as 94.

A lawyer by training, Haswell was born in Dayton, Ohio, on Jan. 30, 1931, went on to earn a bachelor’s degree at the University of Wisconsin in 1953, and graduated from the University of Wisconsin’s law school in 1958.

After that came work in Chicago, including a short stint at Illinois Central as well as work as a public defender and in private practice. He displayed an early penchant for supporting various causes. One of them became the passenger train, hence his organization in 1967 of NARP, now known as the Rail Passengers Association. In his youth, Haswell had enjoyed family trips to Tucson, Ariz., aboard the jointly operated Rock Island/Southern Pacific Golden State and felt personally stung when the train was dropped in 1968.

Haswell and his nascent organization shifted its focus to the Los Angeles-New Orleans Sunset Limited, SP’s heretofore premier train, which the railroad had sharply downgraded, as evidenced by its going coach-only and replacing its dining service with SP’s infamous automat car. Haswell and NARP took SP to court and eventually won a reprieve for dining and sleeping-car service.

Haswell and his team continued their crusade by moving NARP’s offices to Washington, D.C., where the organization joined the effort that led to the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 and a concept called Railpax, a public-private corporation to relieve freight railroads from the burden of running passenger trains. The concept led to the creation of Amtrak and its official launch on May 1, 1971.

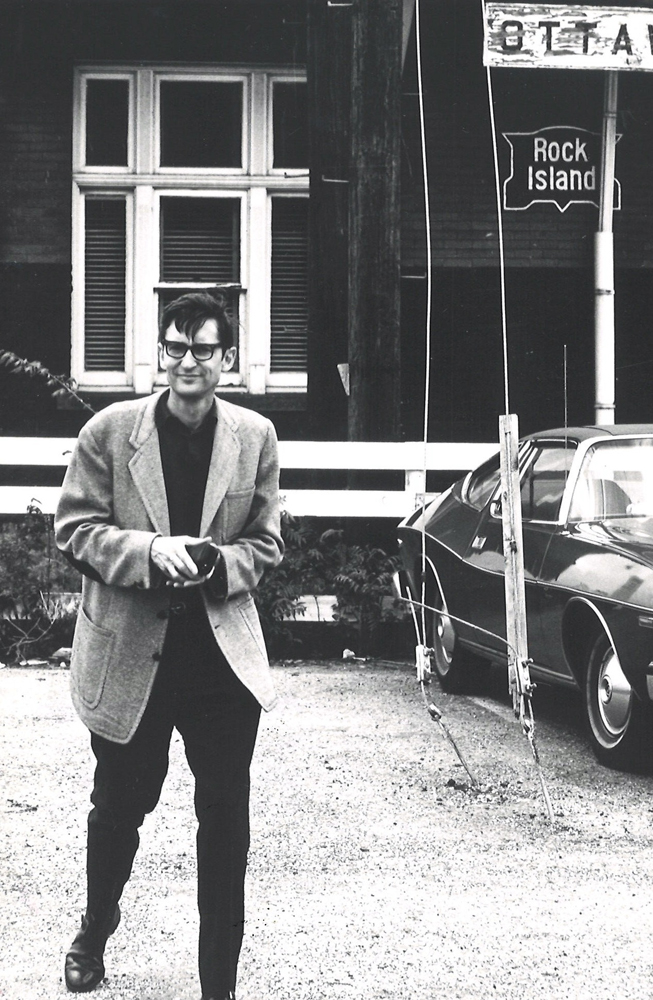

In the early years of Amtrak, Haswell continued to have an influence on events in Washington until 1975, when he took a job as director of passenger operations for the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific, which had opted out of Amtrak and was reeling toward its 1980 liquidation. His stay at Rock Island only lasted two years; the railroad ran its last two intercity passenger trains shortly thereafter.

One person who remembers Haswell’s stint at the Rock was Ed King, a longtime railroad manager and former Trains magazine columnist. King succeeded Haswell in running the remnants of CRI&P passenger service as well as its commuter trains, which eventually were conveyed to Chicago’s Regional Transportation Authority, operated after 1984 as Metra.

“Tony’s tenure was clouded by the fact that he was a passenger-train diehard that put him at odds with the bankrupt Rock,” recalls King. “Whenever there was a dispute between the RTA and the Rock, Tony would take the side of the RTA, effectively biting the hand that fed him.”

Haswell often ran afoul of important people in the industry, certainly railroad executives anxious to shed themselves of passenger trains, and, at least once, the editor of Trains magazine. It came in 1969, when NARP objected to the Milwaukee Road’s petition to discontinue the money-losing Afternoon Hiawatha, its famous Chicago-Twin Cities train. Haswell’s call to suspend the Milwaukee’s petition amounted to, in Editor David P. Morgan’s words, “a kangaroo court.”

“So where does NARP’s man obtain the license for his charge?” asked Morgan in a November 1969 editorial. “It will be a sorry affair if those who conscientiously pursued a clean-window policy are not now allowed their day in court followed by a verdict responsive to the content of that hearing.”

Haswell could be combative. When upon its creation Amtrak elected initially to decline Chicago-Buffalo service, thus skipping the Cleveland market, he saw the oversight in typically blunt terms. “They say there are so few passengers to Cleveland,” Haswell told the New York Times. “The old New York Central did everything short of putting thugs on the train and throwing the passengers off.”

An even-handed assessment of Haswell comes from Kevin McKinney, who founded the magazine Passenger Train Journal in 1968, worked briefly with Haswell in the publication’s early years, and as a publisher followed his career closely. He continues to write a column for PTJ as senior editor.

“If any single person could be called the savior of the American passenger train, it was Haswell,” says McKinney. “Not that the crusader was ever fully satisfied with what he helped create. Although I’m certain that deep down, he felt some gratification knowing passenger trains had survived, including the Sunset Limited, albeit still tri-weekly, he was not happy about the failed promise of Amtrak, a failure that was not his fault, but that of Congress, various administrations, and over the years Amtrak itself.”

Even Trains magazine came around to acknowledging Haswell’s contributions. In its January 2000 turn-of-the-millennium special issue, the magazine recognized Haswell among the century’s 10 leading figures in railroading, a group that included D.W. Brosnan, Al Perlman, and John W. Barriger III. “Every American who rides a train owes a debt to Haswell,” said Trains. “A pain to politicians, railroaders, and union leaders, he was the right man at the right time.”