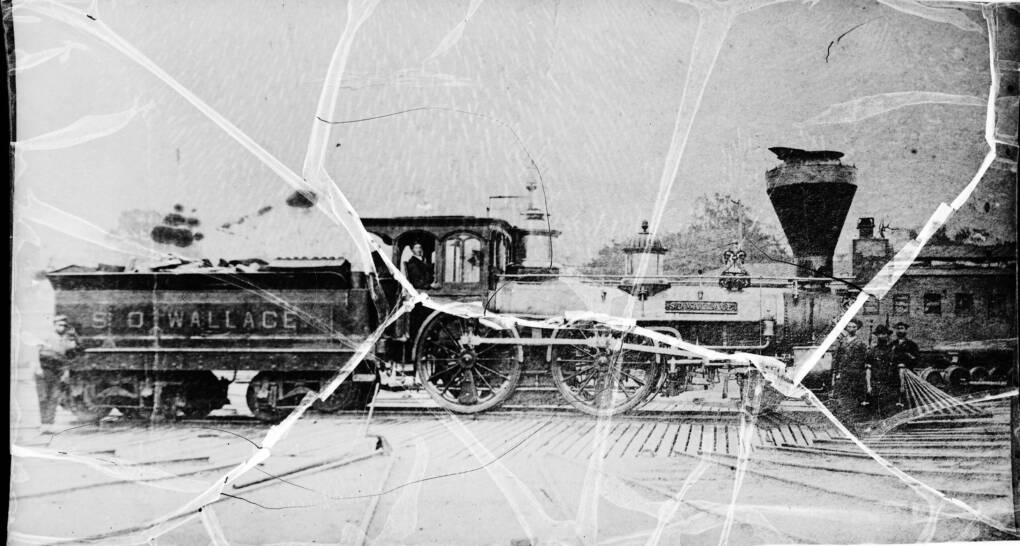

It always bothered me that I couldn’t identify the engineer in this picture of Amtrak train No. 98, departing Main Street Station in Richmond, Va., on Sept. 14, 1974. He wasn’t the regular throttle jockey, whom I knew. Still, it’s one of my favorite images and was used to promote my first book, From the Cab: Stories From a Locomotive Engineer, published in 1999.

I finally reached out to my longtime friend, retired engineer, and Chessie Road Foreman of Engines Teddy “Doc“ Holiday, who said, “That’s Bill Duke. A great passenger engineer [and] probably working a ‘hold down’ (temporary vacancy) after the regular engineer had maxed out his miles.”

Before being directly employed by Amtrak in 1986, I had worked both freight and Amtrak trains on the Seaboard Coast Line. In those days, one of the lesser-known peculiarities of railroading limited the number of miles an engineer could run each month. Mileage was duly noted and tabulated and toward the end of the month, if the engineer had reached a certain limit, he wasn’t allowed to work again until the beginning of the next month.

Recently, so much has been reported about railroad employees not being able to take off when necessary it’s hard to believe, when I was a new hire in the 1970s, I worked with children of the Great Depression who became upset if they were not permitted to work as much as they wished. In all fairness, unlike the practice today, railroads used to maintain an ample “extra list” of unassigned employees to cover vacancies. This rule also applied to conductors in first-in/first-out pool freight service, who had their mileage regulated. It meant increasing, decreasing, or letting stand, the number of crews in the pool. Older employees didn’t want the same-sized pie cut into smaller pieces, whereas more jobs meant work for the younger ones. Once, an old conductor wanted to fight me over a single minute of overtime on our sign-off time. “It may not mean much to you, but that’s 25 cents to me!” he snapped.

Today’s railroaders, thankfully, have never known the despair of the Great Depression. To be clear, the “old heads” loved their home and families as much as anyone, but working every day, including holidays, was the price they paid to keep food on the table, a roof over their heads, and clothes on their backs. Today employees earn higher wages and enjoy much better benefits, but often feel that doesn’t outweigh quality of life issues.

Engineer Bill Duke left Richmond‘s Main Street station for a round trip to Newport News, Va., and back, the day I photographed him. A rare easy job (it consumed only about 6 hours), it allowed him to sleep in his own bed every night. He’d still have to report the 150 miles, and at the end of the month, he might be held off, but I doubt he complained — not like the old timers who urged me, “Make it while you can, because tomorrow, you may be laid off.”

Check out “I saw the light,” a favorite From the Cab column from retired Amtrak Engineer Doug Riddell.