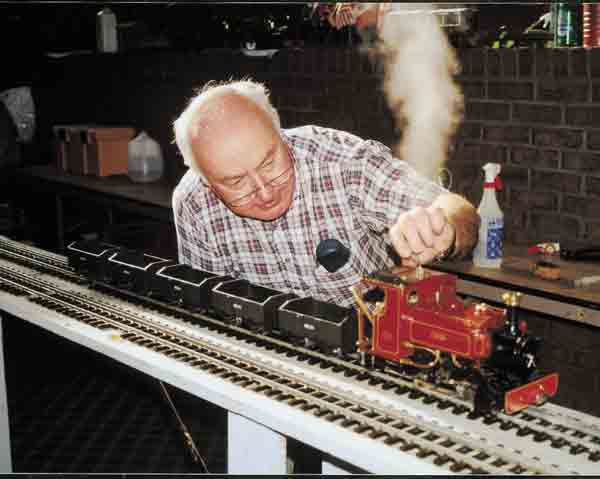

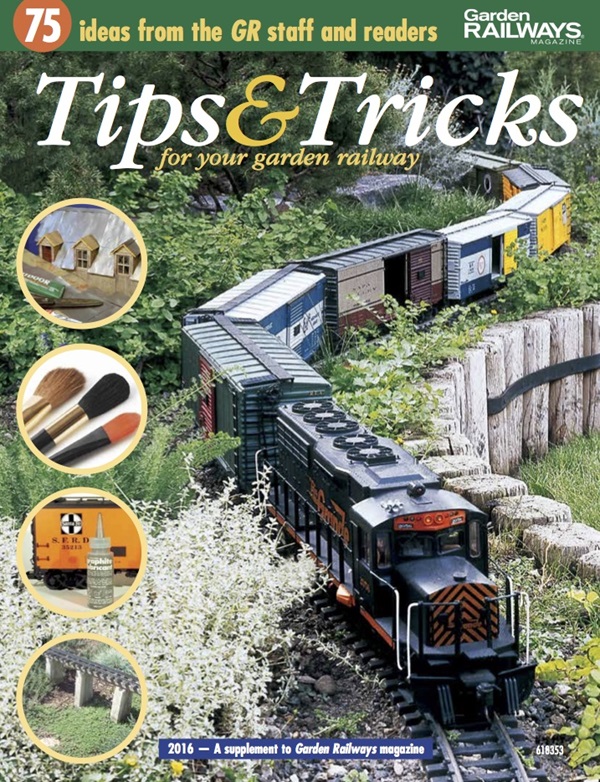

Common questions about live steam locomotives: At model-train shows and garden-railway open houses, live-steam locomotives always seem to gather a crowd of interested onlookers. Our small steam locomotives are new to many people and questions naturally arise. I thought it would be worthwhile to answer some of the most common questions for those of you who are curious about this aspect of the garden-railway hobby.

Are live steamers more expensive than electrically powered locomotives?

A beginner’s live-steam locomotive can be had for well under $500, which is comparable to a number of electrically powered locomotives. Of course, you can spend considerably more for more complicated locomotives. Keep in mind that all live-steam engines are constructed almost entirely from metal, machined and assembled to a high degree of precision, which factors into the cost.

Are they difficult to operate?

They do require more skill to run than an electric locomotive, but they are not difficult to operate. I always say, if you can run an electric train and have operated a gas BBQ, you have the basic skills to successfully run a gas-fired live steamer. You’re doing two activities when you run a gas-fired engine-controlling the fire to make steam to power the locomotive (the fireman’s job) and controlling the speed and direction of the locomotive (the engineer’s job). Each time you run your engine, you will gain more experience in how it behaves in response to your actions and how to get optimum performance out of it.

Can live steamers pull as much as electrically powered locomotives?

The short answer is yes. On level track, both electric and live-steam locomotives of comparable size and weight will pull similar loads. Live steamers are more sensitive to grades, though, and you may find that your live steamer will not pull as heavy a train up a grade as an electric engine.

How long a run can you get out of a live steamer?

Typically, simple live-steam locomotives will run 20 minutes or so on a single filling of water, fuel, and oil. Most are designed so that the fuel (and hence the fire) runs out before the boiler is out of water. This will prevent damage to a dry boiler due to overheating. Stopping to add fuel and water to a live steamer is an entirely prototypical and enjoyable activity, as it gives you hands-on interaction with your locomotive. More sophisticated locomotives carry additional water in the tender and have pumps to add the water to the boiler while it is under steam, allowing for much longer runs.

Do I need special or equipment to operate and maintain them?

Most tools necessary to operate a live steamer can be found in a typical modeler’s toolbox. More specialized tools (say, odd-size wrenches) are often supplied with the locomotives. Well-built live steamers will give many years of service before requiring replacement of worn parts. More often than not, what needs replacing over time are minor things, like washers or O-rings for the filler plug, which can be obtained usually from the locomotive manufacturer, live-steam vendor, or industrial supply house.

Are they safe?

Yes. Locomotives from reputable manufacturers are built to a very high standard, with safety being a top consideration. However, keep in mind that live steamers contain steam under pressure, fired by a butane or alcohol burner. Common sense must prevail. Never tamper with the setting of safety valves and other safety features of a locomotive.

If in doubt, always seek the advice of an experienced live-steam enthusiast. They will almost certainly be willing to help you and will likely be able to answer your questions about live steam, and you might just learn a trick or two that will make running your own locomotive even more enjoyable.

Is the large price difference in locomotives ($400-$5,000+) because of a difference in quality?

Most (if not all) small-scale-live-steam locomotives produced today are built to a high standard. The difference in price comes primarily from the complexity of the model locomotive. Entry-level 0-4-0 locomotives, for instance, which are often freelance models without a lot of detail or features, cost the least. A large engine that is an accurate scale model, with a wealth of detail and a number of features (including correct-scale valve gear, a tender pump, etc.), will be at the top end of the price range.

My new live steamer sprays water up the stack and is difficult to move at the start of run. Is this normal?

Yes. At the start of run, when steam first enters the cold cylinders, it immediately condenses into water. With the cylinders full of water instead of steam, the locomotive won’t move. Once the cylinders are warmed up, the steam does not condense and the locomotive moves normally. Full-size locomotives, as well as some more sophisticated models, have cylinder drain cocks that allow the water to be drained from the cylinders until they are warm. With most little live steamers, you must gently move the locomotive back and forth along the track for a few feet to force the water from the cylinders.

I’ve found that buying the small lighter-refill butane canisters for my gas-fired locomotive is expensive. Is there a more economical source?

Butane can be purchased in larger canisters at significantly lower prices from a number of other sources. These are sold in camping/outdoor supply stores as a fuel for certain types of cooking stoves. The canisters have a screw thread for use with the stoves, so an adapter must be used to fill the locomotive’s gas tank. Adapters are readily obtainable from small-scale-live-steam suppliers. Also, one locomotive manufacturer, Roundhouse Engineering, produces them.

What is the best fuel for small-scale live steamer—gas, alcohol, or coal?

One fuel is not better than another, as each has merits and drawbacks. I like to think of them in terms of the order of complexity. Butane gas is the fuel that the most locomotives use today. It is perhaps the easiest to use and is ideally suited for beginners. Alcohol (usually denatured ethyl alcohol) requires a bit more skill, as the wicks must be set up and maintained well so that they produce a proper flame. Alcohol, unlike gas, burns silently. Unfortunately, an alcohol flame is almost impossible to see in bright sunlight. Coal is the most prototypically accurate fuel for a live-steam locomotive, but it is the most complicated to use. Certain skills must be learned to produce a good, even-burning coal fire. Also, a fair amount of interaction from the operator is required during a run, as the fire must be stoked with coal every 10 minutes or so. And, of course, the ashpan and smokebox must been emptied of cinders, and the fire tubes cleaned with a brush at the end of each run.

Years ago at our local train shows someone was selling a live steam engine for O gauge. I was worried about it derailing and tumping over on its side and setting fire to the layout. Do they have something that cuts off the fire if they derail ang fall over?