The breakthrough

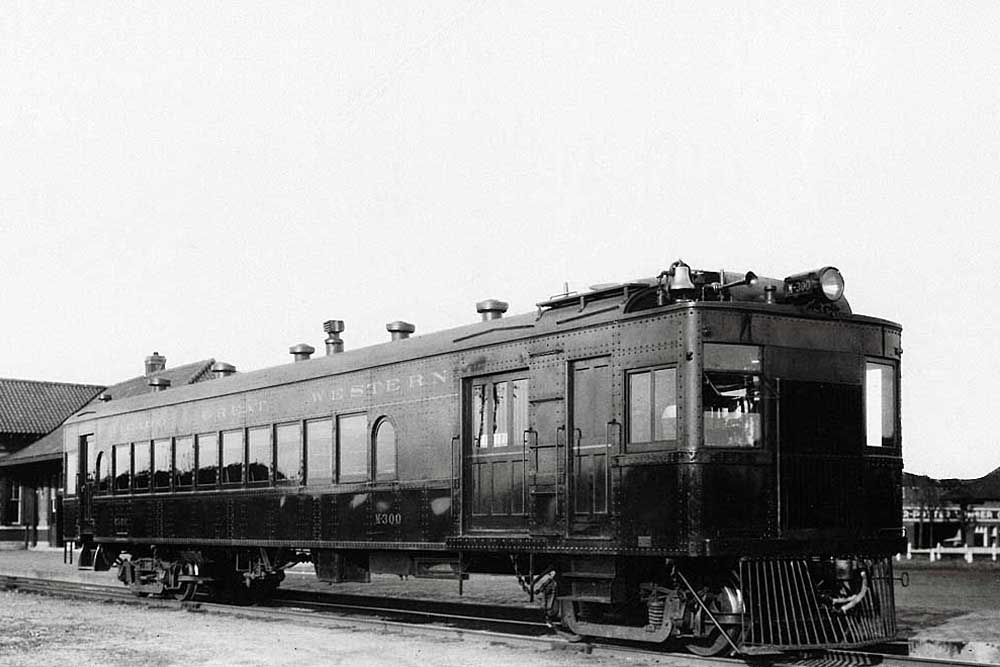

The first Electro-Motive doodlebug motorcar to be delivered went to the Chicago Great Western in August 1924. Right from the first run, founder Hal Hamilton’s expectation that railroads would overload the equipment was confirmed.

The gas-electric car and its transmission system had been rated and advertised as being capable of handling a 35-ton trailing coach, adequate for the unpowered trailer Electro-Motive offered. But the general manager of the CGW elected to accompany the new gas-electric on its first trip and coupled his 85-ton business car to it. Fortunately, there were no problems on the run to Oelwein, Iowa, but Hamilton was kept busy checking the main generator’s temperature as the car handled the ruling grades on the line.

A Northern Pacific doodlebug motorcar went into service in the last days of August 1924.

Both cars passed their performance and braking tests on the respective railroads, confirming the accuracy of the design calculations made by the Electro-Motive staff. The field-service people were kept very busy riding and supporting the needs of the new cars for the tense 30-day performance guarantee period. Hamilton said, “It does not require much imagination to bring out how thin the ice was under us. A plugged gasoline line, broken spark plug, dirt in the air brake system, a brake shoe falling off, or any simple thing could result in failure.”

Hamilton’s next move was to deal with the hostility and reluctance on the part of the railroad mechanical departments to accept the new technology. Thus was the beginning of the resident District Engineer concept: Electro-Motive field-service employees stationed at the customer’s shops to provide direct technical support. It has remained a standard practice by Electro-Motive and the other locomotive builders ever since.

Experience with the cars demonstrated that a gas-electric with a trailer coach could handle branchline operations at a cost of $0.30-$0.40 a mile, compared with typical operating expense of $0.75 to $1.25 for a steam locomotive with coaches. Orders for the new cars began to come in and Electro-Motive was on the way to becoming a successful business. To keep up with the pace of purchases, builders Pullman, Standard Steel Car, and Osgood Bradley were enlisted for manufacturing help.

The problems

Hamilton was secure in the knowledge a high degree of standardization in the gas-electric cars would result in the minimum possible requirements for supporting inventory. Electro-Motive could stockpile essential parts at its home warehouse or at field locations. One spare each of the critical items could provide local protection against random failures because the equipment was the same on each of the cars.

What he had not anticipated was the possibility of a fleetwide field-service problem involving critical propulsion system components on all the cars. This happened with the traction motors relatively early in production, requiring factory repair of many motors. It kept the field service staff busy for months. Further problems were identified and dealt with, but proved to be passing irritants and had little influence on the new product’s success.

Hamilton’s expectation that the railroad would misuse the cars had been reinforced by the experience of the initial trip on the Chicago Great Western. However, he had underestimated how completely some of the railroads might misapply them.

“In the design of the equipment we had accomplished our part of the job, but we were defeated in our efforts to sell the railroad on using the cars as we had planned (i.e. to provide an economical service that would generate new business),” Hamilton said in his writings for Electro-Motive’s 25th anniversary in 1947. “Instead, they insisted on substituting them for the locomotive and head-end car of the little steam trains they had been operating. This meant that the motor car became a power plant, mail compartment, and baggage space with an occasional small passenger compartment for smoking use.

“Behind this they hauled the same coach or coaches which in endless instances had been on that particular local run when all the current travelers were children. The railroads simply treated the motor cars as a loss-reducer…”

Hamilton added, “The net result of this trend of events was that the motor car would become more and more of a locomotive with less revenue space and more and more standard cars being hauled behind it. Therefore, we were under pressure for more and more horsepower until we hit 900 in a single unit.”

Electro-Motive management took note and in 1930 developed a small gas-electric switching locomotive, the Model 60, powered by a Winton Model 148 gasoline engine rated at 400 hp. The electrical transmission system was provided by General Electric, with a single main generator powering four traction motors.

In essence, Hamilton admitted that his concept had been a failure, even though the product had been a success.

By the early 1930s the railroads had purchased 500 of the doodlebug motorcars, virtually all of them being misused. EMC had, however, achieved a much greater goal than simply making a successful product: It had propelled itself into recognition as a respected motive-power supplier.

how far is the GM&O’s longest run from Bloomington to Kansas City? You left this out.

Now if he hadn’t done it–would anyone else have–o would we still have Steam around today?

GE had built a line of gas-electric cars in the previous decade. J G Brill, better known for streetcars and interurbans, was testing the waters. Pullman would come in too.